Patient-Centered Payment for Primary Care

The Services Delivered by Primary Care Practices

High-quality primary care is an essential component of a high-value healthcare system.1 However, designing a payment system that successfully supports high-quality primary care is challenging because “primary care” is not one service but several different services. Since patients have different needs and different preferences for how their needs should be addressed, each patient will need and want to receive different types and numbers of these primary care services. As a result, “high quality primary care” will mean different things to different patients.

Primary care practices deliver three basic types of services2:

Wellness Care. Primary care practices help patients stay healthy by educating them about what they should do to maintain and improve their health and by ensuring that patients have obtained appropriate preventive care services, such as vaccinations and cancer screenings.

Chronic Condition Management. For patients who have one or more chronic diseases or long-term health problems, primary care practices not only prescribe appropriate treatments but also help patients understand how best to manage their condition(s) in a way that minimizes the number and severity of complications and slows the progression of the disease.

Non-Emergency Acute Care. For patients who experience a new symptom or have an injury that does not require emergency care, the primary care practice can either diagnose and treat the problem or arrange for appropriate testing and treatment from other healthcare providers.

There are some fundamental differences in the ways primary care practices need to deliver the services in these categories:

Acute care is inherently a reactive service – a patient only receives the service if they have an injury or experience a new symptom. Even if the problem is not an emergency, diagnosis and treatment should occur as soon as possible to prevent more serious problems from occurring and to minimize time away from work, school, etc.

In contrast, wellness care and chronic condition management should be primarily proactive, i.e., the goal should be to prevent health problems and chronic disease exacerbations before they occur, and to identify new health problems and treat them in early stages, rather than only taking action after a problem occurs or when the patient experiences an unrelated acute event.

In order to be effective, proactive and reactive services must be organized differently, and they must be customized appropriately to patients’ specific needs. Different skills and staff are needed to deliver the services in each category in the most efficient and effective way. As a result, the costs incurred by a primary care practice will depend on the number of patients who receive each type of service.

In addition, although all primary care practices deliver a basic level of services in each of the three categories, practices vary in terms of the scope of the services they offer. For example:

some primary care practices perform basic laboratory testing in the office, but others do not, and some perform more types of procedures (e.g., minor surgery or treatments for specific health conditions) than others. This depends on a variety of factors, including the availability of other providers in the community and the adequacy of payments.

some primary care practices also deliver services such as maternity care and psychological counseling, particularly in rural areas where there are no specialty medicine practices that deliver those services.

Not every patient will need these additional services, so different patients will be affected differently by whether a practice offers them; conversely, a practice’s ability to offer the services will depend on how many patients are likely to use them.

The Problems with Fee-for-Service Payment

Most primary care practices are paid on a fee-for-service basis, i.e., when the practice delivers a specific service to a patient, the practice receives a pre-defined fee associated with that service from the patient or their insurance plan.

In principle, fee-for-service payment can be very patient-centered, since the amount of payment the primary care practice receives will be customized to the specific types of services patients actually receive. Unfortunately, because of two problems in the way Medicare and health insurance plans have implemented fee-for-service payments for primary care, most primary care practices lose money when they deliver appropriate, high-quality primary care services:

There are no fees at all for many important primary care services, particularly services needed for proactive care. Traditionally, fees have only been paid for face-to-face office visits with physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants and for procedures or tests; there has been little or no payment for phone calls and emails with patients or for education and assistance delivered by nurses and other practice staff to provide proactive care management.

The fee amounts are less than what it costs to deliver high-quality care. Primary care practices have generally been forced to spend less time with patients than is necessary or desirable because the fees paid per visit are too low to allow longer visits. Moreover, because the practice has to fill its schedule with patients each day in order to receive enough revenue to cover its costs, patients have difficulty obtaining an appointment or contacting their regular physician.

There are two additional problems with standard fee-for-service payment systems that can harm the quality of care for patients as well as cause financial problems for the primary care practice:

There is no assurance of the appropriateness or quality of the service that is delivered. Under fee-for-service payment, the primary care practice is paid for delivering a service to a patient even if the service was unnecessary, and the fee is the same regardless of the quality vof the service.

The primary care practice is penalized financially when patients are healthy. Because most fees are paid for treating and diagnosing health problems, if the primary care practice successfully helps a patient to stay healthy, it will receive fewer payments for that patient, and potentially no payments at all.

A truly patient-centered payment system must correct all of these problems in order for primary care practices to deliver high-quality care to all types of patients

Problems With Current and Proposed Payment Reforms

To date, three basic approaches have been used or proposed as alternatives to standard fee-for-service payments: (1) pay for performance and shared savings; (2) fees for additional services; and (3) population-based payment. As explained below, none of these approaches solves the problems in current fee-for-service systems3 or enables the delivery of patient-centered primary care.

Pay for Performance

Under this approach, a primary care practice can receive additional payments if it performs better than other practices on a set of payer-defined measures of quality, utilization, or spending, and its payments may be reduced if its performance is lower than what other practices achieve on these measures. This approach has been unsuccessful in improving either the quality or financial sustainability of primary care because it does not solve any of the problems with fee-for-service payment described above:

- There are no new fees for currently unpaid services. The primary care practice is still paid only for the same types of services that have been paid for in the past, and it loses money if it delivers care in different ways.

- Payments still fall short of the cost of quality care. Even if a practice qualifies for additional payments, the increase is typically too small to make up the shortfall between fee-for-service payments and the cost of delivering high-quality care. Moreover, the administrative burdens associated with quality measurement can cause the practice’s costs to increase more than the additional revenue it receives from performance-based payments.

- The measures used do not accurately or completely assess the quality of care delivered. Quality is assessed based on whether care for a patient met a general standard of quality, even if meeting the standard would have been undesirable or harmful for that particular patient. Moreover, because quality measures are only applicable to a narrow range of health conditions and services, there is no measure of quality at all for many types of health problems and patients.

- The primary care practice can be penalized if performance on a measure was poor due to factors outside of the practice’s control. For example, if a patient is unable to afford the services needed to achieve a good result on the quality measure (e.g., medications needed to treat diabetes), or if they are unwilling to use those services, the primary care practice will be scored as having failed on the measure for that patient and its payments may be reduced, even though the practice had no control over the factors affecting that patient’s adherence.

- There is no assurance of quality care for each patient. In addition, a primary care practice that scores well on a quality measure is still paid if it delivers poor-quality care for an individual patient. In fact, since performance-based payments are based on the percentage of all patients whose care met the quality standard, a practice may be paid more for delivering poor-quality care to an individual patient if the practice has higher-than-average quality scores for its other patients.

The most problematic versions of pay-for-performance are “shared savings” payment models that make additional payments to the primary care practice if the payer calculates that the total amount it spent on all of the healthcare services the patients received (including services from hospitals, specialists, etc.) was reduced or was lower than the amount it spent on similar patients who received care from other primary care practices. These payment models have all of the problems described above, plus a serious additional problem:

- The primary care practice can be paid more for withholding services the patient needs. Under a shared savings payment model, if a physician does not order a test, procedure, or medication for a patient, that is considered “savings,” regardless of whether the patient needed the service or not, and that physician can receive a portion of the savings. Similarly, if the physician orders a less expensive test, procedure, or medication than what is really required to address the patient’s health needs, that is also considered savings, and the physician practice may receive a financial bonus.

Fees for Additional Services

In recent years, Medicare and other payers have begun paying primary care practices for some additional types of services, including proactive services such as care management for patients with chronic conditions. Beginning in 2020, primary care practices could receive payments for delivering telehealth services to patients in their homes. However, these new payments have failed to fully address the problems in the current payment system:

- New payments are only for a subset of the services patients need. In general, new payments have only been made for narrowly-defined services and/or for specific types of patients. For example, Medicare’s Chronic Care Management payments are only for patients who have two or more chronic conditions, and the primary care practice can only receive the payment for a patient if the practice spends at least 20 minutes delivering services to the patient during the month. When Medicare began paying for telehealth services in 2020, the payments were initially paid only if there was a video connection with the patient, even if the patient did not have access to a computer or smartphone.

- Payment amounts do not cover the cost of delivering high-quality care. If a primary care practice needs to hire additional staff or incur other costs in order to deliver high quality care, it has to receive enough revenue to cover those costs. However, the amounts of additional payments are typically not based on any information about what it will actually cost to deliver the services, particularly in small practices.

- Restrictions intended to prevent inappropriate uses can prevent use of services when they are needed. Creating new fees for specific types of services creates fears that the services will be delivered when they are unnecessary or inappropriate. For example, the fees for telehealth visits that were authorized during the coronavirus pandemic enable a patient’s primary care physician to address certain types of patient needs and problems without requiring the patient to travel to the physician’s office. However, there are concerns that telehealth will be used when the patient could and should be seen in the office or when no visit at all is warranted. Proposed restrictions to prevent inappropriate uses could also prevent telehealth services from being used in appropriate situations.

Population-Based Payment

In a “population-based payment” system, a primary care practice receives a monthly payment for each patient instead of individual fees for office visits. (Some proposed payments would also replace fees for procedures and other services delivered by the primary care practice). The payments are referred to as “population-based” because the amount of payment depends on how many patients the practice treats, not how many services or what types of services the practices uses to treat them. Population-based payments are similar to traditional capitation payments except that (1) the payment amounts may be higher for individual patients who have more chronic conditions, and (2) the average payment amounts may be adjusted up or down based on quality scores.

Although a monthly payment for each patient gives a primary care practice greater flexibility to deliver different services and a more predictable revenue stream than paying fees for each individual service delivered, this approach fails to solve all of the problems with current payment systems, and it also creates new problems that do not exist under fee-for-service:

- Payments may or may not be sufficient to cover the cost of high-quality care for practices with higher-need patients. Most proposals for capitation and population-based payments set the payment amounts at levels designed to generate the same amount of revenue the practice has been receiving from fee-for-service payments, and in some cases less. This means that if the fee-for-service revenue was inadequate to cover the cost of high-quality care, it is likely that the capitation payments will also be inadequate. In addition, the payments are not adjusted for changes in patients’ acute needs, for the severity of chronic conditions, or for non-medical barriers to care, so a practice may receive even less revenue under population-based payments than it would have under fee-for-service. This could force primary care practices to avoid caring for high-need patients.

- Payments are higher than necessary for patients who need only a small number of primary care services. Even if the monthly payments are adequate on average to cover a practice’s costs, the payment over the course of year for a patient who is healthy will be much higher than what the patient or their insurance plan would have paid under fee-for-service (even if fees had been increased to better cover the costs of delivering high-quality care). That can discourage patients or their employers from participating.

- There is even less assurance that patients will receive high-quality care. As with other pay-for-performance systems, adjusting capitation payments based on average quality performance does not assure that each individual patient receives high-quality care. Moreover, in contrast to fee-for-service, under population-based payment there is no financial penalty to a primary care practice if it delivers fewer services to a patient, and there is no higher payment if the practice’s costs increase, so patients may have greater difficulty receiving services they need.

A Patient-Centered Payment System for Primary Care

Essential Characteristics of a Patient-Centered Payment System

Clearly, a different approach is needed that will actually solve the problems of the current fee-for-service payment system for both primary care practices and patients without causing new problems for either. This section describes the details of a Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment system that has four essential characteristics:

The Payment for Each Patient is Based on the Services That Patient Needs and Wants to Receive. Not every patient will need or want the same services from a primary care practice or to have them delivered in the same way:

- Some healthy patients may want the primary care practice to help them manage their preventive care needs, while others may choose to do that themselves and only use the primary care practice when acute problems arise.

- Some patients with a chronic condition may want the primary care practice to help them manage that condition; others may need or want a specialist to do so.

- Some patients may prefer to receive some services through telehealth methods while others may not want to or be able to do so.

- Some patients may have multiple injuries or acute problems during the year that need diagnosis and treatment, while others may have none.

In Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment, patients (and those paying for their healthcare services) are not expected to pay for services they do not receive; primary care practices are not prevented from delivering sufficient, appropriate services because there is no payment for them; and primary care practices are not expected to provide more or different services to higher-need patients without adequate compensation for doing so.

The Payment for Each Patient Ensures That Each Patient Receives High-Quality Care in the Most Efficient Way. An individual will be far more willing to utilize primary care to maintain their health and address their chronic and acute healthcare problems if they know they will receive the care that is most appropriate for their specific needs. This requires that a primary care practice deliver care to each patient that meets quality standards appropriate for that individual patient. It is also important to deliver high-quality care efficiently, including avoiding the use of unnecessary services and unnecessarily expensive services, and minimizing the amount of time the patient has to spend away from work, school, or other activities.

The Payment Amounts Are Adequate to Cover the Cost of Delivering Services to Each Patient in a High-Quality Way. No business can deliver a high-quality product unless it is paid enough to cover the costs of producing that product; similarly, a primary care practice cannot be expected to deliver the kinds of services each patient needs in a high-quality way unless the payments it receives for its services are sufficient to cover the costs of doing so. The only way to know if payments are adequate is to determine what it costs to deliver high-quality care.

The Payments Are Affordable for Patients With and Without Insurance. Patients can only benefit from high-quality primary care if they use it, and they will only use it if they can afford to do so. A Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment system should make primary care services as affordable as possible for all patients who can benefit from them.

Method of Payment

Different Types of Payments for Different Types of Services

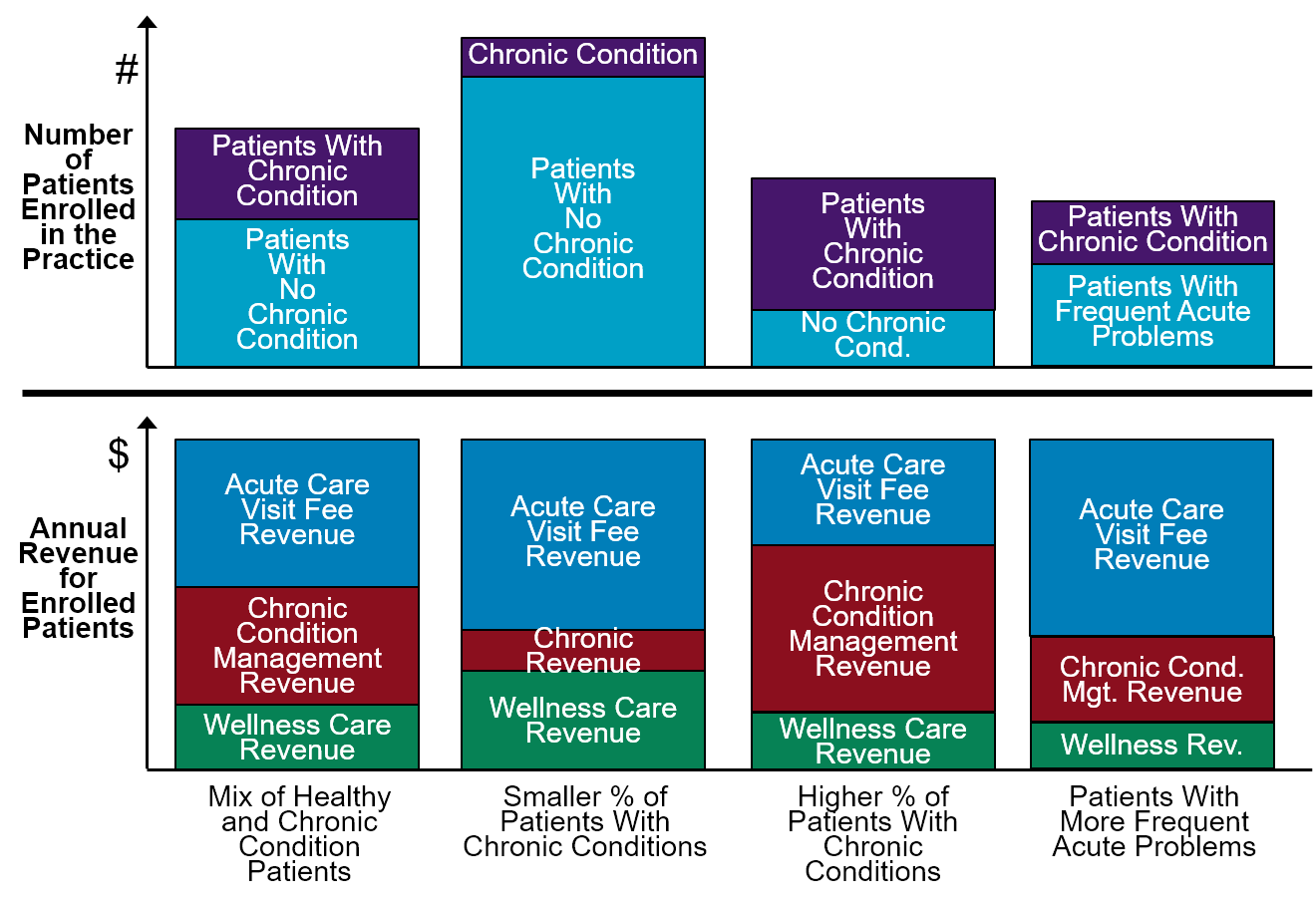

Although every primary care practice delivers preventive care, acute care, and chronic disease care, each of its patients will need a different combination of those services, and different practices will have patients with different sets of needs. Moreover, not every patient will want to receive all of these services from the primary care practice.

Consequently, the most patient-centered way to pay for primary care is to have separate payments for each category of services. Moreover, because the services in each category should be delivered in different ways, different methods of payment will be needed in each category.

Monthly Payments for Wellness Care Management

Maintaining and improving one’s health is a continuous process that occurs throughout the course of each year. Patients who need multiple preventive care services or who have failed to keep up with preventive care will need to take more actions than others during the course of the year, but it will generally be necessary and/or desirable for this to be spread out over a period of time rather than occurring all at once. Consequently, a primary care practice that is assisting individuals with wellness and preventive care will need to be able to provide support to each patient throughout the course of the year.

The nature of the support will differ for different patients. For example, some patients will need or want education and assistance to be delivered in person while others will prefer virtual assistance, and some patients will need more support than others in order to successfully follow a wellness and prevention plan. A key component, however, is proactive outreach to each patient to ensure they understand and are able to obtain the appropriate preventive care and screening services in a way that is feasible for them. In addition, patients who need preventive care services from other providers will generally benefit from having the primary care practice oversee and coordinate those services to avoid duplication and resolve conflicting recommendations.

It is impossible for a primary care practice to deliver this kind of ongoing, customized, proactive wellness support if it is only paid fees for narrowly-defined episodic services such as office visits with physicians. Although some aspects of wellness care must be provided by a physician, many aspects can be delivered effectively by other types of staff in the primary care practice. Consequently, payments for wellness care must provide the flexibility to deliver services in the most effective and efficient way possible.

Since the “service” of wellness care should be continuous and flexible, primary care practices should receive a monthly Wellness Care Payment for each patient. The monthly payment would only be for wellness care management, not for any specific procedures, tests, or treatments the patient needs as part of their wellness plan, such as immunizations, mammograms, colonoscopies, etc. Payment for these other services should be made using separate service-specific fees, as discussed further below.

A patient who does not want wellness care support from the primary care practice should not have to pay for it. For example, some patients may prefer to only receive acute care from the primary care practice, and to obtain all or most of their wellness care from other sources (e.g., from a gynecology practice). Consequently, the primary care practice should only receive a Monthly Wellness Care Payment for a patient who explicitly enrolls with the primary care practice to receive wellness support.

There is at least one group of patients for whom the monthly payment for wellness care will need to be higher because the time involved in helping them will be significantly larger. Patients who have experienced a serious illness or injury and require an extended period of time to regain their health can benefit from assistance from their primary care practice during the recovery process. This is particularly true if there are multiple specialists or other providers involved in the recovery process, since the primary care practice can play an important coordination role. This “transitional care management” is more similar to wellness care management than to either acute care or chronic condition management, but because it is much more intensive, the primary care practice should receive a higher Wellness Care Payment for a patient during a month when they are recovering from a serious illness, injury, or medical procedure. In general, the higher payment would only last for a month, unless the recovery period continues for a longer period of time.

Monthly Payments for Chronic Condition Management

A patient who has been diagnosed with one or more chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes, or hypertension will need to have a treatment plan involving a combination of medications and lifestyle changes that are designed to reduce the severity of symptoms caused by the chronic condition, to prevent exacerbations of the condition and associated complications, and ideally to slow the progression of the disease. Most patients will need education and assistance from the primary care practice in order to design a successful treatment plan and successfully adhere to it, and the practice will need to adjust the plan from time to time as the patient’s needs change and as new evidence about the effectiveness of alternative treatments becomes available. In addition, even with the most effective treatment plan, some patients will experience exacerbations of their condition during the course of the year, and it will be important for the primary care practice to identify those exacerbations as quickly as possible and take appropriate action in order to avoid more serious problems from occurring.

This process of treatment planning, education, assistance, monitoring, and response to problems must be continuous and proactive. Although patients who experience exacerbations will need additional time and assistance from the practice, it is problematic to pay the practice more when exacerbations occur (as is the case in the current fee-for-service system), because the practice is then penalized financially when it is able to prevent exacerbations from occurring. In addition, although development and adjustments to a treatment plan for a chronic condition must generally be done by a physician or other clinician, services such as education, assistance, and monitoring can often be performed effectively by nurses or other types of staff in the primary care practice.

Consequently, payments for chronic condition management need to support continuous care throughout the year, to provide flexibility for services to be delivered in the most effective and efficient way possible, and to encourage prevention of exacerbations. The primary care practice should receive a Monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment for each patient with a chronic condition.

- The patient with one or more chronic conditions will still need basic wellness and preventive care in addition to assistance in managing their chronic conditions, so the monthly payment for chronic condition management would be in addition to the monthly payment for wellness care.

- The monthly payment would only be for chronic care management, not for any specific procedures, tests, or treatments the patient needs as part of their treatment plan; these other services would be paid for through service-specific fees.

Not every patient with a chronic condition will want the primary care practice to provide assistance in managing it. Some patients may need or want to receive that support from another practice that specializes in the patient’s condition(s), particularly patients with severe conditions and patients for whom standard treatments are not effective or have problematic side effects. Consequently, the primary care practice should only receive a monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment for a patient who explicitly enrolls with the primary care practice to receive chronic care management. A patient receiving chronic care management from a specialty practice may still want to receive their general wellness care and acute care from the primary practice (and the specialty practice may be unable or unwilling to provide those other services), so having a monthly payment that is specifically tied to chronic condition management allows the primary care practice to be paid only for preventive care and/or acute care if those are the only services the patient is receiving, while being paid adequately if the patient is receiving all three types of services.

In addition, some patients with a chronic condition may need to temporarily receive proactive management services for that condition from a specialty practice rather than the primary care practice, such as when the patient experiences an acute condition that complicates management of the chronic condition (e.g., the patient becomes pregnant and the medications she had been taking for the chronic condition are problematic during pregnancy). In these cases, the patient can temporarily stop receiving chronic condition management services from the primary care practice and then begin receiving them again when the specialty care is no longer needed. Since the payments are monthly, the primary care practice can receive the monthly payments only during the months when the practice is actually providing the services.

Patients Eligible for Chronic Condition Management Payments

A patient with any chronic disease or long-term condition that requires a significant amount of proactive care should be eligible for this payment. This would include diseases that are commonly the focus of primary care initiatives, such as asthma, COPD, depression, diabetes, and hypertension, as well as chronic conditions that often do not receive appropriate attention, such as chronic migraines, and osteoarthritis. In addition, conditions such as obesity, smoking, and substance abuse should be included since they will require proactive management over an extended period of time.

Trying to precisely define which conditions qualify for the payment will only add administrative burden for the practice and the payer, and will be unlikely to lead to better quality care. It would be better to be inclusive initially, and then later exclude specific types of conditions if they are being used as the basis for billing for chronic care management when it is unlikely that any significant regular or proactive services are needed. If there is evidence that a primary care practice is abusing this flexibility, that practice could be excluded from the Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment system rather than complicating the system for all primary care practices.

Higher Payments for Specific Subgroups of Patients

There are two types of patients for whom the monthly payments will need to be higher because the time involved in chronic condition management will be significantly larger:

Higher Payments for Patients With a Newly Diagnosed or Treated Chronic Condition. A primary care practice will need to spend a significant amount of time with a patient who has been newly diagnosed with a chronic condition in order to develop the most effective treatment plan for the patient and to provide education and assistance to the patient in implementing that plan. A large amount of time will also be needed if a new patient comes to the practice who has been previously diagnosed with the chronic condition by another practice or hospital, but the patient has not been receiving treatment for the condition or the previous treatment has not been effective; in these cases, the primary care practice will need to spend time to ensure the condition has been diagnosed correctly and to design a new treatment plan that will be effective. A higher monthly payment will be needed during at least the initial month following diagnosis or enrollment in order to support this additional time.

Higher Payments for Patients With a Complex Condition. Some patients have a combination of chronic conditions or other characteristics (often referred to as “social determinants of health”) that (1) make it more difficult to develop an appropriate and feasible treatment plan in the first place, and/or (2) make the patient more susceptible to serious exacerbations or complications. For these patients, significantly different or more intensive approaches are needed for preventing exacerbations/complications and for responding when they do occur. Higher payments will be needed to enable adequate time to be spent in providing the more intensive level of care management and assistance these patients require.

Patients should not be considered to have a complex condition simply because they have multiple chronic diseases; many comorbidities occur commonly and primary care practices routinely manage the care of those comorbidities in a coordinated way. For example, a high percentage of patients with diabetes also have hypertension and/or hyperlipidemia, and the appropriate treatment for patients with diabetes includes management of hypertension and hyperlipidemia, so a patient who has two or more of these conditions should not be classified as having a complex condition solely on that basis. On the other hand, a patient who has no chronic diseases other than diabetes, but who has other characteristics that make standard approaches to treatment and management of diabetes very difficult or impossible (e.g., blindness, deafness, paralysis, homelessness, illiteracy, etc.), will require significantly more time and assistance, so such a patient would generally be appropriate for this “complex condition” category. A patient who has two chronic diseases that co-occur less frequently and where the standard approaches to treating each disease can be in conflict would also be appropriate for this category.4

Because of the diversity of factors that can make delivery of care more difficult, no fixed set of eligibility rules should be established for this category; instead the primary care physician should be able to make the determination as to whether an individual patient is appropriate for this category and document the basis for that determination. (Patients with an advanced illness can also be included in this category, but ideally, they should receive comprehensive, multi-disciplinary palliative care services, either from the primary care practice or a palliative care provider, that are supported by payments specifically designed for palliative care.)

Fees for Non-Emergency Acute Events

Patients who are receiving good preventive care and chronic disease management will still have accidental injuries and acute illnesses such as colds or urinary tract infections during the course of the year that are not emergencies and can be effectively treated by a primary care practice. In addition, many patients will experience symptoms such as pain, dizziness, or fever that could be caused by either a minor or major health problem, and a primary care practice can and should promptly diagnose the cause of such problems and determine what, if any, treatment is needed. In general, these acute events will require some type of “visit” with the primary care physician, either in person or through a video or audio connection, in order to determine an accurate diagnosis and prescribe appropriate treatment.

Since acute events will occur unpredictably during the course of the year, the primary care practice needs to be staffed and organized in a way that enables it to provide these visits quickly when a patient does experience such an event. This means that the practice will have to incur a minimum level of cost every week to maintain that readiness even if relatively few of its patients actually experience an acute event during the course of the week. From the primary care practice’s perspective, it might seem that a monthly payment for each patient would be preferable to visit-based payments because it would provide a more predictable revenue stream that would better match the costs for staff and facilities that it would incur on a regular basis. However, the practice may also need to incur extra costs (such as additional hours for part-time staff or overtime for salaried staff) if a relatively large number of patients need care during the week, and a monthly payment would provide no additional revenue to cover these extra costs.

From the patient’s (and payer’s) perspective, a monthly payment would mean that patients who experience many acute events would be paying less than the cost of the services they received, and patients who experience few or no acute events would effectively be paying for services they did not need or receive and subsidizing the care of those who did have many acute events. Moreover, if patients pay nothing extra for a visit, some of them will likely request visits more often than necessary, and if the practice’s revenue did not depend on how many visits it scheduled, it would have a much weaker incentive to see patients quickly. As a result, monthly payments are not a patient-centered approach to payment for acute care.

In contrast to preventive care and chronic care, acute care is fundamentally reactive, episodic, and short-term in nature, so the primary care practice should receive an Acute Care Visit Fee when it provides diagnosis and treatment for a new acute event affecting a patient.

Although diagnosing and treating a new acute event requires some kind of “visit” with the patient, this is different than what has traditionally been described as a “visit-based payment” in fee-for-service systems:

- Patients who are receiving preventive care and/or chronic condition management services from the practice will likely also have visits with practice staff related to those services, but the cost of those visits will be supported by the monthly Wellness Care and Chronic Condition Management Payments. In contrast, if a patient with a chronic condition has an acute event such as an injury or a new symptom that they have not experienced before, the practice should be paid an additional amount for the visit needed to diagnose and treat that acute problem.

- Conversely, the fact that an additional fee is paid specifically for a visit to diagnose and treat an acute problem does not mean that the visit to the practice has to be limited to the acute problem. It may well be convenient for the primary care practice to address some of the patient’s wellness care or chronic condition management needs on the same day that an acute problem is being addressed, and it may be necessary or appropriate to do so if changes in wellness care or chronic condition management are needed because of the acute event. This will require the practice to spend more time with the patient than what would have been necessary solely to address the acute issue, but if the patient has enrolled with the practice for wellness care or chronic condition management, that extra time would be supported through the monthly Wellness Care and Chronic Condition Management Payments, not through the Acute Care Visit fee.

The Acute Care Visit Fee should be designed to allow sufficient time for the physician to examine the patient, correctly diagnose the condition, and develop an appropriate treatment plan through a shared decision-making process with the patient. This can generally be done in 30 minutes for most types of acute problems that typically arise in primary care. If the physician needs to spend significantly more time than this because of the complexity of the specific acute issue that is being addressed, then the physician would be paid two Acute Care Visit Fees. If it was appropriate for the patient to return for a second visit for the same acute problem (e.g., to verify that a prescribed medication had fully addressed the problem), then there would be a second Acute Care Visit Fee for that second visit. This would be a simpler, more straightforward process than trying to define different payment amounts for different amounts of time, and it would avoid creating a financial penalty for a physician who spends adequate time to address the patient’s needs during a single visit rather than asking the patient to come back for second visit on another day.

Acute Care Visit Fees for Patients Receiving Chronic Condition Management Services

The Acute Care Visit Fee should not be paid if the patient’s problem is clearly an exacerbation of a chronic disease and if the practice is receiving a monthly Chronic Care Management Payment for the patient, since the monthly payment is intended to cover the costs of both preventing exacerbations of the chronic disease and addressing exacerbations when they occur. For example, if the patient has asthma, and the practice is receiving a monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment specifically for asthma, then if the patient experiences an asthma attack and needs assistance or treatment from the primary care practice, the primary practice would not receive an Acute Care Visit Fee for providing that assistance/treatment. In fact, high-quality care for asthma includes development by the practice and patient of an “asthma action plan” defining what the patient and practice will do to prevent and treat asthma attacks, and one of the elements of the plan will likely be to specifically encourage the patient to contact the practice as soon as possible when an asthma attack appears to be occurring, rather than waiting until it becomes severe.

There will be many cases in which it will be uncertain whether a particular acute problem was caused by a patient’s chronic disease, and there will also be cases in which the acute problem triggers an exacerbation of the chronic disease. In these cases, the primary care practice should have the discretion to bill for an Acute Care Visit Fee depending on what they believe is most appropriate in the circumstances. Trying to precisely define which situations qualify as acute events and which do not will only add administrative burden for the practice and the payer, and will be unlikely to lead to better quality care. If there is evidence that a primary care practice is abusing this flexibility, that practice could be excluded from the Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment system rather than complicating the system for all primary care practices.

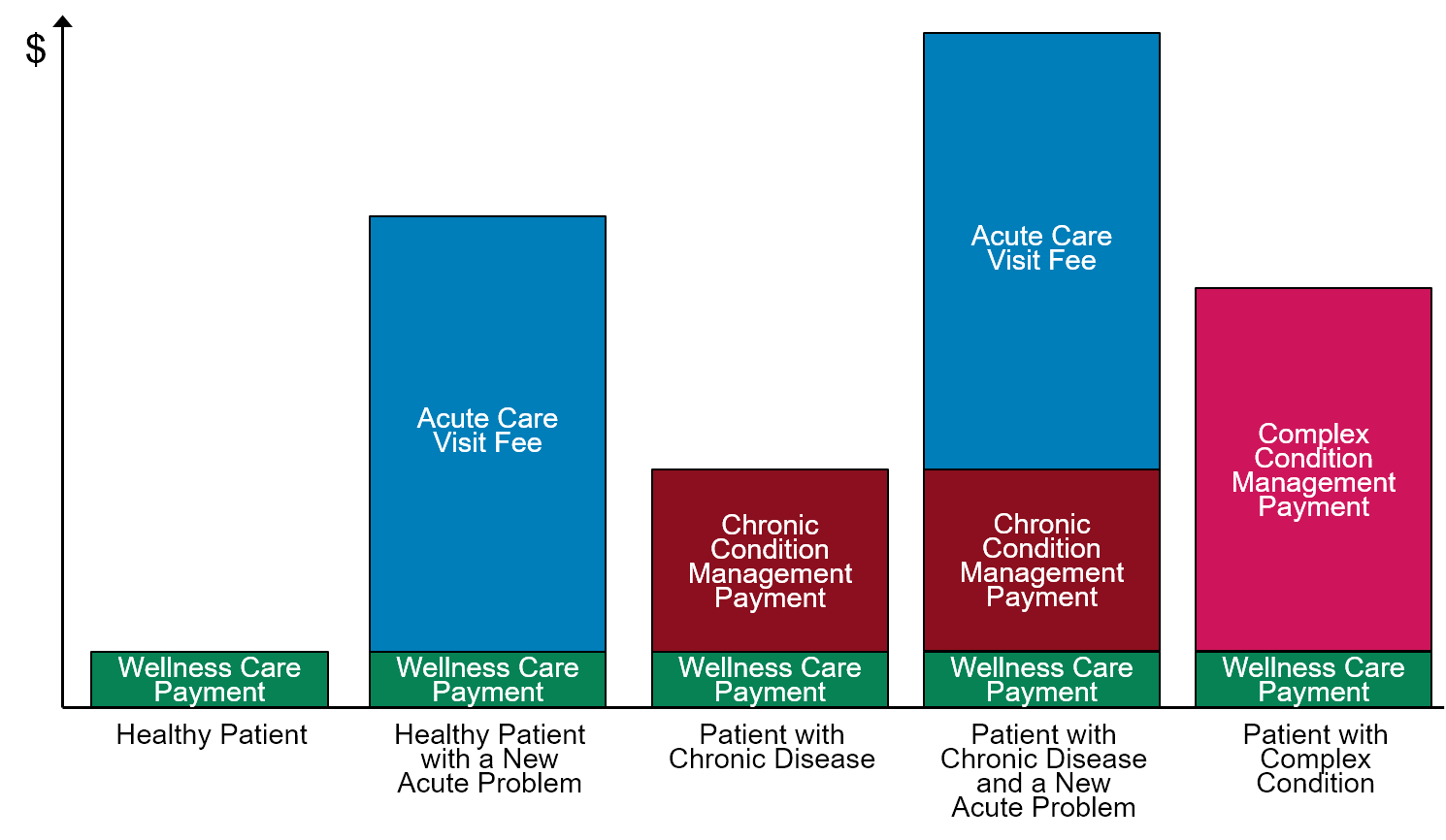

Need for Further Risk Adjustment

As shown in Figure 1, the additional monthly payments for patients with chronic conditions, the higher monthly payments for patients with complex conditions, and the additional fees for patients with new acute problems result in the practice receiving a higher total payment during the month for a patient who has greater needs. This is analogous to what is accomplished in population-based payment systems where a single monthly payment for the patient is “risk adjusted” based on characteristics of the patient.

FIGURE 1

Differences in Monthly Primary Care Practice Revenues

for Different Types of Patients

However, in most risk adjustment systems, there is no change in the payment amount for a patient who has an acute problem, for a patient with a newly diagnosed chronic disease, or for a patient who has non-medical characteristics that make their care more complex. As a result, the payments to the primary care practice under Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment would better match the actual differences in the time that a primary care practice would spend with different patients.

Fees for Individual Procedures and Tests

The payments described above are designed to pay for three specific types of services – wellness care, management of chronic conditions, and visits to diagnose and prescribe treatment for new acute care issues. As part of the treatment or management plans developed in any of these areas, the primary care practice may perform a procedure such as an immunization or injection, a suture or excision, or therapy for a chronic condition. It is beneficial for a patient to be able to receive these procedures from the primary care practice when feasible and appropriate, since it avoids the need to make a separate trip to another physician or facility and helps ensure that the patient receives the appropriate procedure in a timely way.

At a minimum, performing one of these procedures will require additional time from the primary care physician or other practice staff beyond what they would otherwise need to spend with that patient, and in most cases, the practice will need to incur out-of-pocket costs for medications, supplies, or equipment in order to perform the procedure. If the primary care practice does not receive sufficient revenue to cover the additional time and cost associated with performing these procedures, it will be unable or unwilling to deliver them.

In addition, it is helpful if the patient can receive basic laboratory tests at the practice, such as measurements of the patient’s cholesterol or blood sugar levels, rather than having to make a separate trip to a laboratory and then potentially having to make a separate visit or contact with the primary care practice in order to receive the appropriate treatment based on the result of the test. Most of the common tests ordered by primary care practices can be performed at the primary care practice using equipment and chemicals designed for that purpose without any special licensing. However, there is a fixed cost for acquiring the testing equipment, there is a cost for the chemicals needed for each test, and time is needed to have the test performed by a trained staff member. If the primary care practice does not receive sufficient revenue to cover these costs, it will be unable or unwilling to perform them.

Since only a subset of patients will need these procedures and tests and since the cost of performing each procedure and test will differ, the primary care practice should receive an additional fee when an individual patient receives a procedure or test. The amount of the fee should be adequate to cover the costs of delivering that type of procedure or test.

Payments for Integrated Behavioral Health Services

There is growing recognition that primary care practices need the ability to deliver some types of behavioral health services so that patients who have both behavioral health needs and physical health needs can have them treated and managed in a coordinated way. Although primary care physicians can and do provide a basic level of behavioral health counseling to patients as part of office visits for other medical issues when needed, many primary care practices have not had appropriate staff to provide additional or more intensive behavioral health services to patients because of barriers in the current payment system – either there is no payment at all for such services, or the payments that do exist are too small and/or too narrowly defined to support the kinds of services the primary care practice would be able to deliver.5

There are two basic approaches for delivering behavioral health services in primary care practices – the Collaborative Care (IMPACT) Model6 and the Primary Care Behaviorist Model.7 Both of these models are based on having one or more individuals with behavioral health expertise working for the practice who can provide in-person and/or virtual counseling and care management to patients with a suspected or diagnosed behavioral health problem such as depression, anxiety, or substance use disorder. Patients with severe conditions would need to be referred to a specialized behavioral health care provider rather than receiving treatment from the primary care practice, but the primary care practice’s behavioral health staff could help ensure that the care the practice is providing for these patients’ physical health problems is coordinated with the behavioral health treatment they receive from the other provider(s).

It is problematic to pay for these integrated behavioral health approaches using fees for counseling sessions. There is typically a high no-show rate for such sessions that can cause fee-based revenues to fall below the cost of employing the counseling staff, and paying fees for individual sessions can encourage scheduling more sessions than necessary. In addition, it is important to enable primary care physicians to make a “warm handoff” to the behavioral health staff when a patient visits the practice for medical reasons and the physician identifies the need for behavioral health care. This can only occur if the behavioral health staff’s schedule is not completely filled each day, and under a fee-based system, open time on the schedule means a loss of revenue.

Monthly payments would provide the practice with predictable revenue to support integrated behavioral health services and the ability to maintain open times on the schedule. However, it would be undesirable if monthly payments were limited to patients who have been formally diagnosed with a behavioral health condition; the physician should not be forced to assign a formal “mental health” diagnosis to a patient if they believe that would be problematic for the patient or if the physician is not sure what diagnosis to assign.

The most appropriate approach would be to treat basic behavioral healthcare services as an additional component of the primary care practice’s wellness care services, since many patients will need some level of behavioral health support at some point in time. A primary care practice that delivers integrated behavioral health services should receive a monthly Integrated Behavioral Healthcare Payment in addition to the monthly Wellness Care Payment for each of the patients who has enrolled for wellness care from the practice.

Payments for New Patients

The payments for wellness care and chronic condition management described above would only be for patients who explicitly enroll with the practice to receive these proactive services on an ongoing basis. A primary care practice will want to ensure that it can meet a patient’s needs before enrolling them for ongoing services, and the patient may be unwilling to enroll until they have a chance to discuss with the physician whether the practice will deliver the services the patient needs in a way that is convenient for the patient. Consequently, most new patients will need at least one initial visit with the practice before enrollment occurs.

The current fee for service system pays a higher amount for the initial visit with a new patient than for visits with established patients, and the initial visit payment is higher for new patients who have multiple, complex problems than for those who do not. There does not seem to be any compelling reason to change this approach to paying for the initial visit, since if the practice can meet the patient’s needs, it will be in both the practice’s interest and the patient’s interest for the patient to enroll with the practice and begin receiving the proactive, high-quality care that would be supported by the monthly payments for enrolled patients.

Payments for Services to Non-Enrolled Patients

Patients who are unwilling or unable to enroll with a primary care practice for ongoing wellness care or chronic condition management services may still want or need to receive occasional services for acute conditions, chronic condition exacerbations, etc. If a primary care practice provides a service to one of these patients, the practice should be paid for doing so; current fee-for-service payments can continue to be used for this purpose.

Billing and Payment for Services

The simplest and best way to operationalize the new payments for wellness care, acute care, chronic condition care, and behavioral healthcare for patients who have health insurance is to create a billing code for each of the new payments. Each of these services/payments would need to be assigned a CPT® (Current Procedural Terminology) code by the American Medical Association’s CPT Editorial Panel. Alternatively, HCPCS (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System) Level II Codes could be created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) HCPCS Workgroup. New CPT codes and HCPCS codes are created every year in order to allow physician practices to bill for new types of procedures and services,

Specifically:

- A new CPT code (“XX010”) would be created to represent one month of Wellness Care services for a patient who has explicitly enrolled with the practice to receive wellness and preventive care. An additional CPT code (“XX011”) would be created to allow a higher payment during the month for a patient who has been discharged from a hospital or is recovering from a serious illness.

- A new CPT code (“XX020”) would be created to represent a visit in which a patient receives diagnosis and treatment planning services for a new acute symptom or problem. (The “visit” could either be in person or through electronic means, as appropriate.)

- A new CPT code (“XX031”) would be created to represent one month of Chronic Condition Management services for a patient who has explicitly enrolled with the practice to receive these services. An additional CPT code (“XX030”) would be created to allow a higher payment during the initial month of care for a patient with a newly diagnosed/treated chronic condition, and another CPT code (“XX032”) would be created to allow higher payment on an ongoing basis for patients who have a complex condition.

- A new CPT code (“XX012”) or a code modifier (“XX010-BH”) would be created to provide an additional monthly payment for each patient who has enrolled in the primary practice for wellness care if the practice has the capacity to deliver integrated behavioral health services.

The definitions of the new CPT codes should not specify exactly what wellness or chronic condition management services the patient would have to receive during the month or what services must be provided during the acute care visit in order for the practice to be paid. In particular, the practice should have the flexibility to deliver services in person or through electronic means, to have services delivered by the physician, a nurse, or other member of the practice staff, etc. Section 4-C describes the method that would be used to ensure that appropriate care was being delivered in return for payment.

The physician would make the determination as to which specific CPT code was appropriate based on the patient’s characteristics and the type of service being delivered. For example, if the physician determined that the patient had a complex chronic condition that was eligible for the higher chronic condition management payment, the physician would bill using the appropriate code, while maintaining appropriate documentation for doing so in the patient’s clinical record.

The primary care practice would submit the appropriate CPT code to a patient’s health plan when that patient received wellness care, acute care, or chronic care management services from the practice, and the health plan would pay the practice the amount assigned to each of those codes (Section 4-D discusses how the payment amounts should be determined). For example:

- If a patient who is enrolled only for wellness care receives no other services during the month, the practice would submit a bill with the XX010 code to the patient’s health plan for the month.

- If a patient who is enrolled for wellness care also visits the practice for an acute problem, the practice would submit a bill with both the XX010 and XX020 codes. If the patient also receives a procedure to address the acute problem, the practice would include the appropriate billing code for that procedure on the claim form in addition to the other codes.

- If a patient has a chronic disease and enrolls with the practice for chronic condition management, the practice would submit a bill each month with both the XX010 and XX031 codes.

- If a patient has not enrolled with the practice for ongoing wellness care or chronic condition management services and the practice delivered a procedure or other service to the patient, then the practice would bill for that service the same way it does today using the appropriate existing billing code for the service.

Since new CPT and HCPCS codes are created every year, every physician practice’s billing system has the capability to use new codes, and every health insurance company’s claims payment system has the capability of processing claims with new codes, so this approach would involve minimal administrative costs for the primary care practice and the health insurance company.

If a primary care practice submits the monthly billing code for either Wellness Care or Chronic Condition Management, it would not bill for any of the current CPT codes for Evaluation and Management (E/M) services to established patients (i.e., 99211-99215) during that month. If the health insurance plan received a claim with one of these codes and also a claim with an XX01x, XX02x, or XX03x code for the same patient during the month, it would only pay for the latter codes.

Enrollment of Patients

The primary care practice would only be eligible to receive the new payments for patients who had enrolled with the practice to receive ongoing services, so the practice would only submit a claim form with one of the new billing codes for a patient if that patient had, in fact, enrolled with the practice for ongoing care. The practice would only be eligible to receive chronic condition management payments for a patient if they had an eligible chronic condition, so the practice would only submit billing codes for chronic condition management if the practice had diagnosed the patient with a chronic condition and the patient had agreed to receive regular, proactive care management for that condition from the practice.

The enrollment process should be carried out by the primary care practice, not by the patient’s health insurance company. No patient should be “attributed” to the practice by a health insurance company without the knowledge and consent of the patient and the primary care practice. A patient would have to explicitly tell the primary care practice that it wanted to enroll to receive proactive care from that practice, and the practice would need to ensure that it had the capacity to provide the appropriate services to address the patient’s needs before agreeing to enroll that patient.

It will be important for patients to understand that enrolling with the primary care practice to receive proactive wellness care or chronic care management services from the practice does not mean that the primary care physician will be serving as a “gatekeeper” who will determine whether the patient can receive any other kind of services, unless the patient has enrolled in an HMO-type insurance plan and the primary care practice has agreed to play the gatekeeper role for patients in that insurance plan.

The practice would inform the patient’s health insurance company that the patient had enrolled by submitting claims for the monthly wellness care and/or chronic condition management payments.8 This process is far less burdensome for both the primary care practice and the health plan than the complex and problematic attribution systems that have been used by Medicare and other payers to make monthly “population-based payments” to primary care practices.

A patient should also be able to disenroll from receiving proactive care from the practice if they are no longer able or willing to receive it. Since the wellness care and chronic condition management payments would be billed for and paid monthly, a patient could disenroll at the end of any month if they wished to, and the primary care practice would then stop submitting bills for the monthly payments for that patient. As discussed earlier, it may be appropriate for some patients to stop receiving chronic condition management services from the practice temporarily while they are receiving services for that condition from a specialty practice (e.g., during pregnancy), and the monthly payment structure easily allows that to occur.

Accountability for Quality and Utilization

The second key characteristic of a Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment system is ensuring that each patient receives high-quality care in the most efficient way. This can only be done if there is a clear definition of what “quality care” from a primary care practice means for each individual patient and if there is a mechanism for assuring that quality care is being provided without the use of unnecessary and unnecessarily-expensive services.

The Problems With “Outcome-Based Payment”

Although it would seem ideal to evaluate the quality of a patient’s primary care services based on whether the services produced a good outcome for the patient, this is impractical to do for several reasons:

- Primary care practices provide care to patients with a large number of health problems and a diversity of needs and preferences. There is no single “outcome” that would be appropriate for all patients.9

- There are no outcome measures at all for many conditions commonly managed by primary care practices, and where there are, it is generally agreed that outcomes must be assessed through multiple measures rather than one single outcome measure. For example, an international effort to define outcomes for diabetes resulted in a list of 27 separate outcome measures, ranging from glycemic control to psychological well-being.10

- In general, even when an outcome measure has been developed, there is no standard defining the minimum outcome that a primary care practice could be expected to achieve or the timeframe in which an outcome should be expected to occur. For example, in the consensus document on diabetes outcome measures, no target values were defined even for things that are routinely measured, such as blood pressure, body-mass index, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). In general, it is impossible or inappropriate to expect the same outcomes for every patient because of the many differences in characteristics of patients that can affect treatment outcomes. The consensus document on diabetes outcomes defines 16 different variables needed to adjust the outcome measures in order to compare outcomes for different groups of patients.11

- When attempts are made to define target values for an individual outcome measure, they can result in worse overall outcomes for some patients. For example, diabetes quality measures have typically defined a single HbA1c target level for most or all diabetic patients, even though there is clear evidence that it is neither feasible nor desirable for every patient to achieve the same HbA1c level, and overly-aggressive efforts to reduce patients’ HbA1c levels to achieve these targets have caused serious problems for some patients.12

- Performance on most outcome measures is affected not just by the services delivered by the primary care practice, but by the willingness and ability of a patient to do what is necessary to achieve the outcome. For example, a primary care practice can prescribe appropriate medications for diabetes and encourage patients to take them, but the practice cannot force patients to do so, and a large percentage of patients do not take the medications needed to control their disease.13 Consequently, even if a desirable, patient-appropriate outcome target could be defined for an individual patient, it would be inappropriate to hold the primary care practice responsible for failure to achieve that target without controlling for the patient’s own contributions.

A Bad Alternative: Quality Measures

Even though a primary care practice cannot be held directly accountable for whether good outcomes are achieved, one would still want the practice to plan and deliver the services to each patient that are most likely to result in a good outcome for that patient.

If there is strong clinical evidence that a particular set of services will result in the best outcome for a particular patient, then it is reasonable to expect the practice to deliver those evidence-based services to the patient, or at least attempt to do so. Similarly, where there is evidence that a particular set of services is ineffective or harmful, it is reasonable to expect that a practice will avoid delivering or ordering those services, even if the patient might want to receive them.

This has led to a proliferation of quality measures, each intended to measure whether a specific aspect of a primary care practice’s services is consistent with one or more pieces of evidence regarding the right way to diagnose or treat a specific health problem. However, this approach has been ineffective in improving quality14, burdensome for primary care practices15, and potentially harmful to patients.16 Some of the reasons for this include:

- Most quality measures are based on whether a specific approach to services has been used or a specific standard of quality has been met for all patients who have a particular disease or are in a specific demographic group, even when evidence clearly indicates that different services or standards are appropriate or necessary for a significant subset of those patients.17 As a result, one cannot expect any primary care practice to meet these quality measures 100% of the time, and there is no way to determine whether a difference in performance between practices is due to differences in the characteristics of the patients they treat or differences in the actual quality of care they deliver.

- The quality measures typically define a specific threshold to distinguish “good quality” care from “poor quality care.” The only thing that affects the measure is the number of patients on either side of that threshold, so care can get worse for the patients who are receiving “good” care and care can get better for patients who were receiving “poor” care without causing any change at all in the quality measure.

- If the patient is unwilling to accept the services required to meet the quality measure, or if there are barriers that prevent the patient from obtaining those services (e.g., an allergy to a medication or inability to afford the medication), then the primary care practice will need to deliver or order alternative services. Most quality measures provide no mechanism for excluding these patients from the measure, so care that is more consistent with patient preferences and needs can appear to be worse on the quality measures.

Because primary care practices deliver care for a wide range of different health problems and a wide variety of patients, measuring quality in this way for every problem and every type of patient would require hundreds of different measures. The burden that using a large number of measures causes for primary care practices has led to efforts to reduce the number of measures used, but this does not resolve the problems with the individual measures nor does it provide any way to assure quality for the many patients whose care is not measured at all.

Another Bad Alternative: Prior Authorization

For many types of health problems and patients, there is no clear evidence as to what services are effective and which will result in the best outcome for particular types of patients. As a result, some physicians use far more services, or far more expensive services, than others. There may be no evidence to support this, but there may also be no evidence showing that it is harmful.

In an effort to prevent primary care practices from ordering or delivering unnecessary and unnecessarily-expensive services, many health insurance companies require a primary care physician to obtain “prior authorization” from the insurance company before the company will pay for certain kinds of medications, tests, or procedures ordered or delivered by the physician. These prior authorization processes are extremely problematic18 for several reasons:

- If there is no clear evidence to guide the physician’s decision about which services to use, there is also no clear evidence to guide the health insurance company’s decision, and the insurance company has far less information about the patient’s symptoms, history, and characteristics to inform its decision than the physician does.

- As a result, there will still be variation in what services are delivered, but the variation will be driven by differences in the prior authorization rules and decisions made by different health plans, rather than differences in patient needs.

- Seeking prior authorizations from health plans and challenging inappropriate denials by the health plans requires the primary care practice to spend a large amount of time and money19 that does nothing to improve patient care. It also requires the health plan to spend money on staff to review and decide on prior authorization requests. There is no evidence that the savings, if any, from reductions in unnecessary services justifies the costs incurred by both payers and primary care practices.

- Most prior authorization requests are ultimately approved, so the process merely delays the delivery of care the patients would have received anyway. In some cases, these delays can lead to bad outcomes for patients.

A Better Way: Using CPGs/SCAMPs and SAINTs

Guidelines, Pathways, and SCAMPs

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) represent a more comprehensive, efficient, and patient-centered mechanism for achieving good patient outcomes than a list of quality measures. A clinical practice guideline assembles all of the available evidence regarding how to diagnose a symptom or treat a condition in a way that is likely to achieve the best outcome for each patient.20 Moreover, in contrast to the one-size-fits-all nature of quality measures, a CPG encourages and guides appropriate customization of services to patients with different characteristics based on available evidence.

Since clinical practice guidelines define which services are inappropriate as well as which services are appropriate, they can reduce use of unnecessary services in a more patient-centered way than burdensome and problematic prior authorization processes. In order to reduce variation, the guidelines can include a recommended option when there are multiple diagnostic or treatment choices and the available evidence does not indicate which option is better. The term “Clinical Pathway” is often used to describe a set of guidelines that recommend the use of a specific approach when the evidence is unclear or where multiple options have equivalent benefit.21

Clinical practice guidelines and pathways have been successfully used to improve quality and reduce variation in a variety of settings22, and studies have found that primary care physicians would be willing to use guidelines if they are designed and implemented appropriately.23 In order to avoid re-creating the problems of quality measures and prior authorization, effective clinical guidelines/pathways for primary care need to meet four criteria:

- Ease of Use. The guidelines must be structured so they are easy for primary care physicians to use. The most useful versions of guidelines/pathways are integrated directly into the physician’s EHR (so they do not require re-entering data about the patient), they address all of the inter-related decisions the physician will be making (e.g., about both diagnosis and treatment) rather than forcing the physician to consult multiple separate guidelines, and they are structured as flowcharts or decision trees so the physician can quickly determine which specific recommendations are most applicable for the specific patient the physician is treating.

- Ability to Deviate. Physicians must have the ability to depart from the guidelines/pathway when there are good reasons to do so.24 For many types of patients, there is not strong evidence as to what approach to diagnosis or treatment would achieve the best result, so no guideline can dictate what should be done for every patient.25 In particular, when patients have multiple chronic conditions, guidelines designed for care of individual diseases may not be appropriate.26 In addition, the patient may be unwilling or unable to accept the services recommended by evidence, in which case a different set of services will be needed.

- Documentation for Deviations from Guidelines. In order to use evidence where it is applicable and to reduce unnecessary variation, deviations from the guidelines/pathways should only occur for good reasons. Consequently, there must be a mechanism for physicians to document the reasons for deviation if the guideline is not followed for a specific patient.

- Modification and Expansion of Guidelines. There should also be a process for modifying or expanding guidelines to address the situations where physicians feel the guidelines do not apply or would be problematic for particular types of patients. Clinical data from electronic health records can be collected and analyzed to determine whether the care that was delivered outside the guidelines resulted in good outcomes for the patients, and if so, the guidelines and recommendations can be revised accordingly. This process can generate new evidence more quickly and cost-effectively than randomized control trials, and it may be the only feasible way to generate evidence about how to treat health problems that occur infrequently and patients with special characteristics.

A Standardized Clinical Assessment and Management Plan (SCAMP) is a form of clinical practice guideline/pathway that achieves these goals. It is explicitly designed to allow deviations in appropriate situations. In addition, there is an explicit process for using information about the circumstances and reasons for deviations and the outcomes of those choices in order to improve the guidelines.27 SCAMPs have been successfully used to improve guidelines and outcomes for patients in a number of areas such as evaluating chest pain, diagnosing food allergies, etc.28

To be successful in supporting patient-centered care, CPGs and SCAMPs must be developed and refined by clinicians, not by health plans. Clinicians will be more likely to utilize and adhere to clinician-developed CPGs/SCAMPs than rules or pathways developed by payers or other entities where cost considerations may have taken precedence over patient outcomes in defining recommendations.29 In addition, a CPG/SCAMP developed by clinicians can be used for all patients, regardless of payer.

A SAINT

Although greater use of CPGs/SCAMPs in primary care would likely result in greater use of evidence-based services and reduce the use of unnecessary services, this would not be sufficient for achieving the best outcomes for patients, because the CPGs/SCAMPs do not directly ensure that an individual patient’s most important needs are being adequately addressed:

- Although the guidelines can help ensure the right services are being used to diagnose and treat a specific patient problem, the physician has to know the problem exists in order to use the guidelines.

- In addition, the physician needs a way to know whether the patient is actually experiencing better outcomes as a result of the services that are delivered. In most cases, evidence merely indicates that the probability of achieving a good outcome is higher with one set of services than others, not that a better outcome is guaranteed. If services recommended in the guidelines fail to achieve better outcomes for a particular patient, a different approach will be needed. SCAMPs allow deviations from the guidelines in these situations, but there must also be a way to determine whether the alternative approaches resulted in good outcomes so that the guidelines can be modified appropriately.

- Most evidence-based guidelines are focused on one particular symptom or condition, and they may provide little or no guidance as to what will work best for patients who have multiple conditions. Even if each of the condition-specific approaches recommended by guidelines would be desirable, it may be impractical or impossible for a patient who has multiple conditions to take all of those actions or receive all of those services simultaneously. A method is needed for prioritizing which evidence-based actions to take and which to defer or ignore based on the goals that are most important to the patient.

Consequently, in addition to CPGs/SCAMPs, a primary care practice needs a Standardized Assessment, Information, and Networking Technology (SAINT). A SAINT provides a systematic way for a patient to provide their primary care practice with actionable information about any physical and emotional problems they are having and whether the services the practice is providing to the patient are addressing the issues that are of most concern to the patient.30

A successful SAINT will have the following characteristics:31

- Easy to Use and Affordable for the Primary Care Practice. The SAINT must allow the primary care practice to both collect and access information about patients’ needs in a way that does not require a large amount of time by the primary care physician and other practice staff and does not require a significant upfront or ongoing cost in terms of equipment and software.

- Provides Timely, Actionable Information to Guide Care. The information provided by the SAINT needs to tell the practice whether the patient has a problem now, rather than what problems may have existed in the past, and the information needs to be specific enough to allow the practice to determine what initial action to take in response.

- Enables and Encourages Patient Participation. Ideally, the primary care practice would receive information from all of the patients in the practice. However, because the information describes problems and priorities from the patients’ perspective, patients have to be both willing and able to provide the information. This not only means the SAINT has to be easy for patients to use, but patients need to feel that submitting the information will actually result in better care, and they must not be concerned that the information will be inappropriately shared or misused in any way.32

How’s Your Health is a SAINT designed specifically for primary care that meets all of these criteria:

- It operates through a web-based platform (www.HowsYourHealth.org) that is free for primary care practices and easy for patients to use.

- It generates a summary measure called the What Matters Index (WMI) that identifies which patients are experiencing problems and assesses key patient outcomes.33 The WMI has been shown to predict health care spending as well or better than other commonly-used risk stratification/prediction tools.34

- It enables patients to identify specific risk factors, concerns about their health, and problems they have had getting appropriate help so the primary care practice can better plan how to assist them.35 It can serve as the Health Risk Assessment required as part of the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit.36