Overview of Patient-Centered Payment

The Problems with Current Payment Systems

Fee-for-Service Payment

Most healthcare providers (physicians, hospitals, laboratories, etc.) are currently paid on a fee-for-service basis, i.e., when the provider delivers a specific service to a patient, the provider receives a pre-defined fee associated with that service.

The Problems With Fee-for-Service Payment

Fee-for-service payment has been widely criticized because it “rewards volume instead of value,” but a much more precise definition of the problems with fee-for-service payment is needed in order to ensure that an alternative approach to payment would actually be better, not just different.

One major problem with fee-for-service payment is that there are large gaps in the types and amounts of fees Medicare and health insurance plans pay:

- There are no fees at all for many important healthcare services, particularly services needed for proactive care. Traditionally, fees have only been paid for face-to-face office visits with physicians and for procedures or tests; there has been little or no payment for phone calls and emails with patients, for education and proactive care management by nurses, community health workers, and pharmacists, for palliative care services, and for non-medical services such as transportation. If payments are not available for ambulatory or home-based care, patients have to obtain care in hospitals or other expensive settings.

- The fee amounts are often less than what it costs to deliver high-quality care. Physicians have generally been forced to spend less time with patients than is necessary or desirable because the fees paid per visit are too low to allow longer visits. This can force the patient to make additional visits or result in misdiagnoses or complications that increase the cost of care. Hospitals do not receive adequate payments to support emergency care and other types of essential standby capacity, and they have to subsidize those losses by delivering extra services or charging more for services.

Not only do current fee-for-service payment systems fail to support all of the services that patients need, they do not assure patients they will receive the highest-quality care:

- There is no assurance of the appropriateness or quality of the service delivered. Under fee-for-service payment, a healthcare provider is paid for delivering a service to a patient even if the service was unnecessary, and the fee is the same regardless of the quality of the service.

- Healthcare providers are penalized financially when they reduce complications and keep patients healthy. Under fee-for-service payment, providers are paid more to treat an infection or complication than to prevent it from occurring. Moreover, because most fees are paid for treating and diagnosing health problems, a primary care practice or specialty care provider who successfully helps a patient to stay healthy will be paid less for that patient, and may not be paid at all.

A third problem occurs when treatment requires multiple services:

- It is impossible for a patient or payer to compare providers based on the cost of treating a health problem. Although the fees for each individual service are known in advance, different combinations of services can be used to treat a particular condition, and the services a provider uses for a specific patient will only be known after the services are delivered. This makes it impossible to compare two providers based on how much it would cost for each of them treat the same health problem. Current efforts to increase transparency about provider prices make it easier to find out what individual services cost, but not what treatment costs in total.

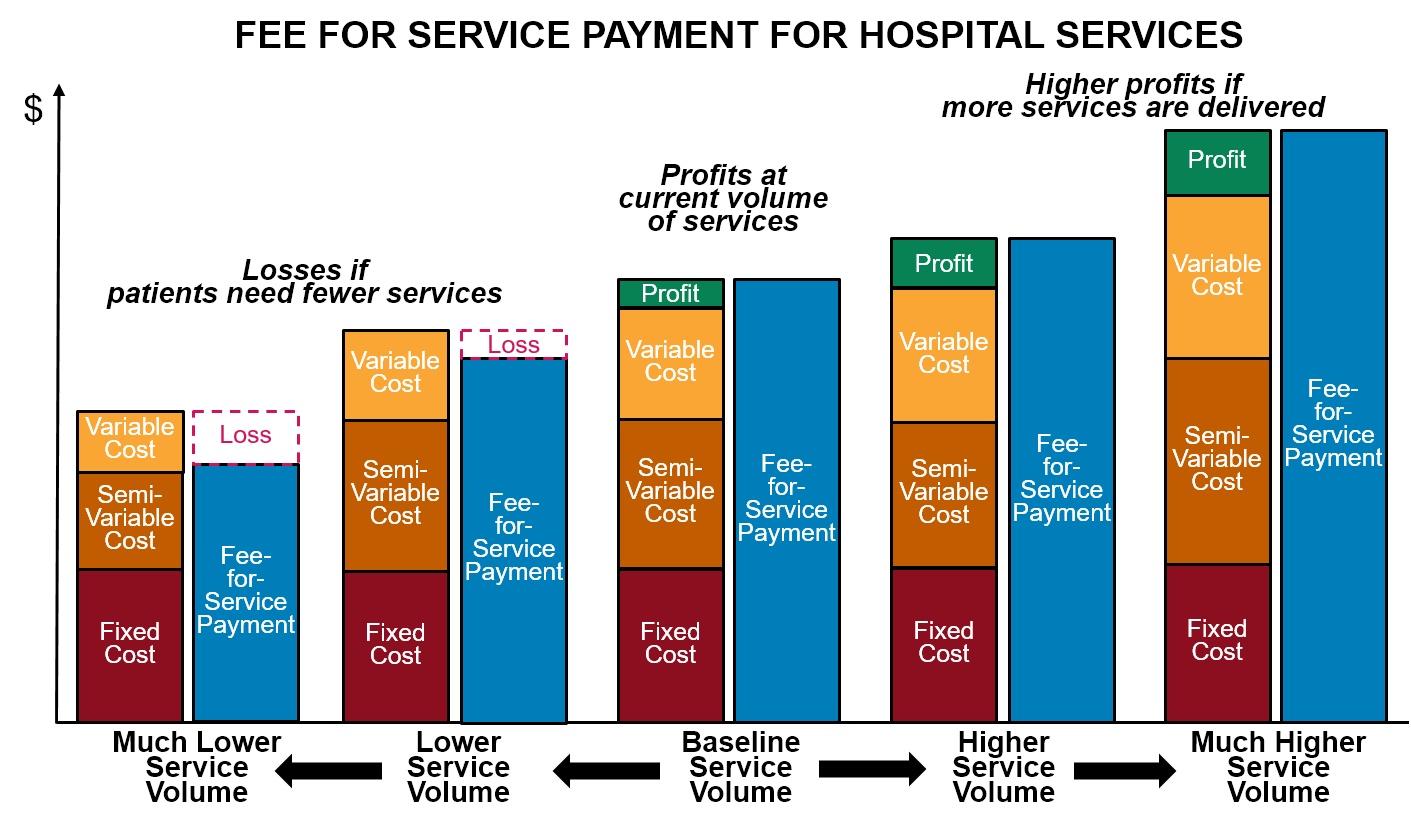

The Strengths of Fee-for-Service Payment

While it is true that fee-for-service payment rewards “volume instead of value,” any payment system that doesn’t support a higher volume of service when more services are needed can result in worse outcomes for patients. Two important strengths of fee-for-service payment are:

- Healthcare providers are paid more for patients who need more services. Under a fee-for-service system, payments to healthcare providers are automatically “risk adjusted” for patients with greater needs.

- A provider is only paid if a patient receives a service. Under fee-for-service payment, patients and payers do not pay a provider if the patient does not receive care.

The problems with fee-for-service payment need to be corrected, but the strengths must also be preserved.

Value-Based Payment

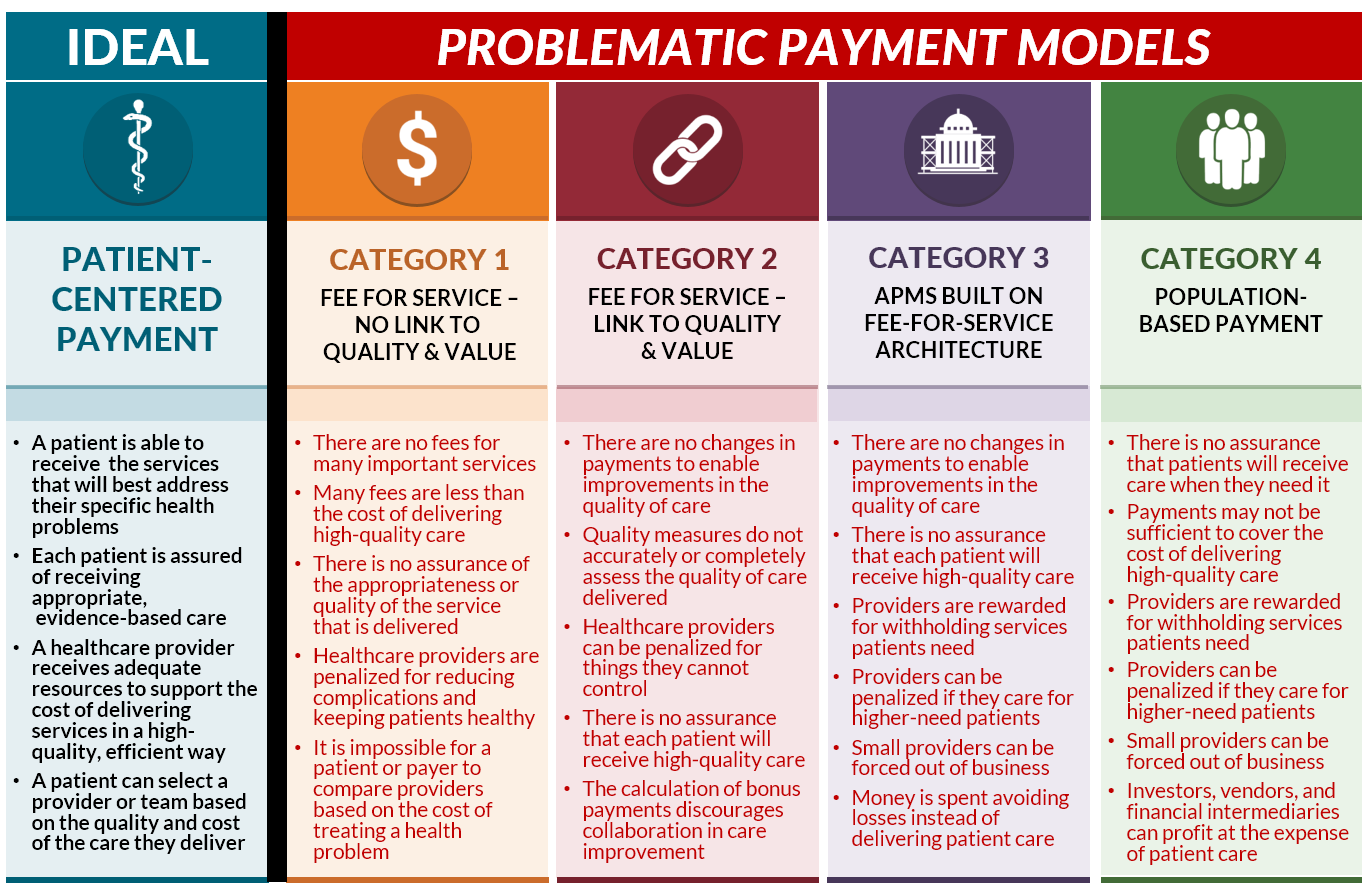

“Value-Based Payment” is a generic term used to describe a payment system where the amount of payment for a service depends in some way on the quality or cost of the service that is delivered. To date, most value-based payment systems have fallen into three general categories:

- Pay for performance.

- Shared savings and downside risk.

- Population-based payments and capitation.

Pay for Performance

The most common approach to value-based payment has been “pay for performance” (P4P). Under this approach, a healthcare provider may receive bonus payments if it performs better than other providers on a set of payer-defined measures of quality, utilization, or spending, and it may have to pay penalties or have its payments reduced if its performance is lower than what other providers achieve on these measures. Most physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers now participate in at least one pay-for-performance system because of the P4P programs created in Medicare, such as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) for physicians, the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program, and the Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing program. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) describes this as “Category 2: Fee for Service with a Link to Quality and Value” (in contrast to “Category 1: Fee for Service - No Link to Quality & Value”).

This approach has been unsuccessful in improving the quality of care for a number of reasons:

- There are no new fees for services that could improve the quality of care. Physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers are still paid only for the same types of services they are paid for under the standard fee-for-service system, and they still lose money if they deliver care in different ways or help patients stay healthier.

- Payments fall short of the cost of delivering quality care. Even if a healthcare provider qualifies for a performance-based payment, the amount is typically too small to make up the shortfall between fee-for-service payments and the cost of delivering high-quality care. Moreover, the administrative burdens associated with quality measurement can cause a provider’s costs to increase more than the additional revenue it receives from performance-based payments.

- The measures used do not accurately or completely assess the quality of care delivered. Quality is assessed based on whether the care for a patient met a general standard of quality, even if meeting the standard would have been undesirable or harmful for that particular patient. Moreover, because quality measures are only applicable to a narrow range of health conditions and services, there is no measure of quality at all for many types of health problems and patients.

- A healthcare provider can be penalized for reasons outside of the provider’s control. For example, if a patient is unable or unwilling to use all of the services needed to achieve a good result on the quality measure (e.g., the patient cannot afford the medications needed to treat their diabetes), the provider will be scored as having failed on the measure for that patient and its payments may be reduced, even though the provider had no control over the factors affecting that patient’s adherence. In many cases, a provider who treats a patient for one health problem can be penalized based on the quality of care that unrelated providers deliver for completely different health problems.

- There is no assurance that each patient will receive high quality care. A healthcare provider is paid for delivering a service to an individual patient that is inappropriate or of poor quality regardless of how the provider scores on quality measures. In fact, since performance-based payments are based on the percentage of patients whose care met the standard in the quality measure, a provider would be paid more for delivering poor-quality care to an individual patient if the provider has higher-than-average quality scores for its other patients.

- The payments discourage collaboration in care improvement. In many P4P programs, such as Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), a provider can only receive a bonus payment for good performance if other providers have been penalized for poor performance. This discourages collaborative efforts to improve care, because if a high-performing provider helps other providers to improve, the high-performer will receive a smaller bonus.

It is often suggested that P4P systems have been unsuccessful because the “incentives aren’t large enough,” but the real problem is they don’t actually solve the problems with fee-for-service payment. Moreover, the simplistic quality measures used in these systems can discourage providers from delivering care to disadvantaged patients who have complex needs or difficulty adhering to standard approaches to treatment.

Shared Savings and Downside Risk

Value-based payment systems have increasingly focused on reducing healthcare spending, rather than improving the quality of care. The most common approach has been “shared savings” payment models. In these programs, a healthcare provider continues receiving standard fees for the services they deliver, but the provider is eligible to receive a bonus payment if the payer determines that total spending on the provider’s patients has decreased or if spending has increased less than the payer expected. A growing number of these models now require “downside risk,” i.e., they require the provider to pay penalties if the payer’s total spending increases or increases by more than the payer expected.

Most of the “alternative payment models” created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are designed this way, including the Medicare Shared Savings Program, the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) program, and the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement program. Providers participating in these programs continue to receive standard fees for individual services, so the payment systems are really just a variation of the pay-for-performance concept. The primary difference from typical P4P programs is that the focus is on reducing spending rather than improving quality, and the amounts of the bonuses and penalties are proportional to changes in spending. This is why CMS describes these payment systems as “Category 3: Alternative Payment Models Built on Fee-for-Service Architecture.”

In general, shared savings and downside risk models have failed to significantly reduce healthcare spending or improve the quality of care because they do not make any fundamental changes in the way healthcare providers are paid:

- There are no payments to support the delivery of new or different services that could reduce the use of more expensive services. There are many opportunities to reduce healthcare spending in ways that do not harm patients or even improve outcomes. In most cases, this can only be done by delivering a different set of services to patients, but those services cannot be provided today because there are no payments to support them under current fee-for-service systems. Since there is no change in the way providers are paid in shared savings and downside risk programs, they cannot afford to do what is necessary to achieve savings without harming patients.

- Payments fall short of the cost of delivering quality care. Even if a healthcare provider qualifies for a shared savings payment, the amount may be too small to cover the cost of the services needed to achieve the savings. Moreover, hospitals and other types of providers incur significant fixed costs to deliver essential services, and as a result, a reduction in the number of services delivered reduces their revenues more than their costs. The shared savings payments may be too small to offset the resulting losses.

- There is no assurance that each patient will receive high quality care. A healthcare provider continues to be paid for delivering a service to an individual patient that is inappropriate or of poor quality. There is no penalty for low-quality care other than a reduction in the bonus payment if savings are generated.

- It is still impossible to compare providers based on the cost of treating health problems. Although shared savings and downside risk payment systems typically calculate an “expected” amount of spending for a procedure or for all of the services delivered during a particular period of time, these calculations are generally made after services are delivered, rather than in advance. Even if the expected spending is defined in advance, the complex calculations needed to determine the bonuses and penalties for providers can generally only be performed after services have been delivered, so the total amount that will actually be paid will not be known in advance.

Of greater concern, however, is that this approach to payment has the potential to harm the quality of care for patients, make it more difficult for high-need patients to access care, and force small healthcare providers out of business:

- Providers are rewarded for withholding services the patient needs. Under a shared savings payment model, if a physician does not order a test, procedure, or medication for a patient, that is considered “savings” regardless of whether the patient needed the service or not, and the physician can receive a bonus payment. The small number of simple quality measures used in these payment models do nothing to protect against most potential types of undertreatment.

- Providers can be penalized if they care for higher-need patients. Patients with higher needs will generally need more services and more expensive services, and the risk adjustment systems used in shared savings models do not adequately address this. The more high-need patients that a provider cares for, the higher the spending that will be assigned to that provider, which will reduce the likelihood of receiving a shared savings bonus and increase the chances that the provider will be financially penalized.

- Providers can be penalized for factors beyond their control. The spending measures used in these payment models generally include spending on all services the patients receive, not just services delivered or ordered by the providers who are at risk, and those providers may have little or no ability to influence whether and how these other services are delivered. Moreover, spending can increase due to increases in the prices of drugs and other services that are beyond the control of the providers in the shared risk payment model. Small physician practices and hospitals do not have adequate financial reserves to pay for these costs and may be force out of business.

- Money is spent on avoiding losses instead of delivering patient care. Providers participating in downside risk models have to spend large amounts of money on data systems, stop-loss insurance, risk score maximization and other activities designed to increase the chances of receiving bonuses and reduce the likelihood of paying penalties, rather than on improving care for patients.

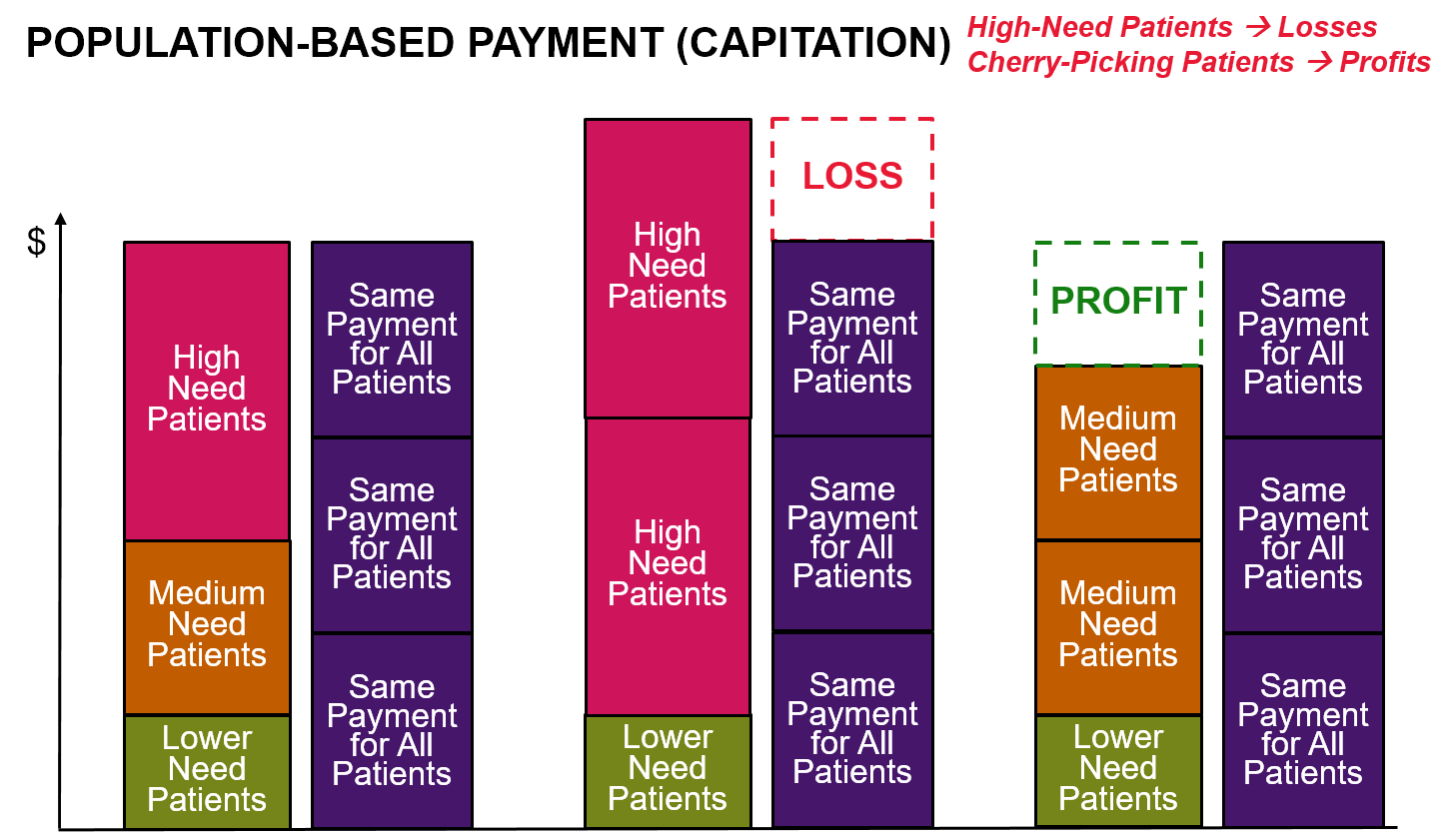

Population-Based Payment and Capitation

“Population-based” payment systems do not pay fees for individual services, but instead pay a healthcare provider a fixed amount each month to provide a patient with as many services as the patient needs. The payments are referred to as “population-based” because the total amount of revenue a provider receives depends on the number of patients the provider is caring for, not how many services or what types of services are used to treat the patients.

Population-based payments are fundamentally the same as traditional capitation payments except that (1) the payment amounts may be higher for individual patients who have more chronic conditions, and (2) the average payment amounts may be adjusted up or down based on measures of quality or spending similar to pay-for-performance and shared savings programs.

A single monthly payment for each patient gives a healthcare provider greater flexibility to deliver different services and a more predictable revenue stream than paying fees for each individual service delivered, and it also makes it easier for a patient or payer to predict how much they will need to pay for care. However, this approach fails to solve all of the problems with current fee-for-service payment systems, and it also creates new problems that do not exist under fee-for-service:

- There is no assurance that patients will receive care when they need it. A strength of fee-for-service payment is that a provider is only paid if they deliver a service to a patient. In contrast, under population-based payment, the provider is paid regardless of whether a patient receives the services they need.

- Payments may not be sufficient to cover the cost of delivering high-quality care. Most proposals for capitation and population-based payments set the payment amounts at levels designed to generate the same amount of revenue the provider has been receiving from fee-for-service payments, and in some cases less. This means that if the fee-for-service revenue was inadequate to cover the cost of high-quality care, it is likely that the capitation payments will also be inadequate.

- Providers are rewarded for withholding services the patient needs. Capitation payments are the same regardless of how many services are delivered or what types of services are delivered, but the provider incurs higher costs when more services are delivered and the provider saves money when fewer services are delivered, so even if the payment is large enough to support all of the services the patient needs, the provider’s profits will be higher if fewer services are delivered. The small number of simple quality measures used in these payment models does nothing to protect against most potential types of undertreatment.

- Providers can be penalized for providing care to higher-need patients. One of the strengths of fee-for-service payment is that providers will be paid for providing additional services to patients who have more healthcare problems. In contrast, typical population-based payment systems make no adjustments in payment for patients with new chronic conditions, for patients with multiple acute problems, or patients who need more or different services because they face non-medical barriers to care. This can penalize providers who care for high-need patients.

- Providers can be penalized for factors beyond their control. In “global” or “comprehensive” population-based payment systems, a physician practice or health system is expected to pay for all of the services a patient needs from the fixed population-based payment. The provider may have little or no ability to control many of the factors that affect the cost of those services, such as increases in the prices of drugs or services that have to be delivered by other providers or health systems. This can further discourage caring for patients who have higher needs and create even stronger incentives to withhold necessary but expensive treatments.

- Investors, vendors, and financial intermediaries can profit at the expense of patient care. Because of the high levels of financial risk associated with population-based payment systems, healthcare providers are forced to pay vendors and consultants to help them identify ways to maximize profits and minimize losses, which reduces the revenues available for healthcare services to patients. Private investors and financial intermediaries can make bigger profits on the fixed capitation payments if they can find ways to cherry-pick patients and increase the risk scores assigned to patients, rather than by improving the quality of healthcare services.

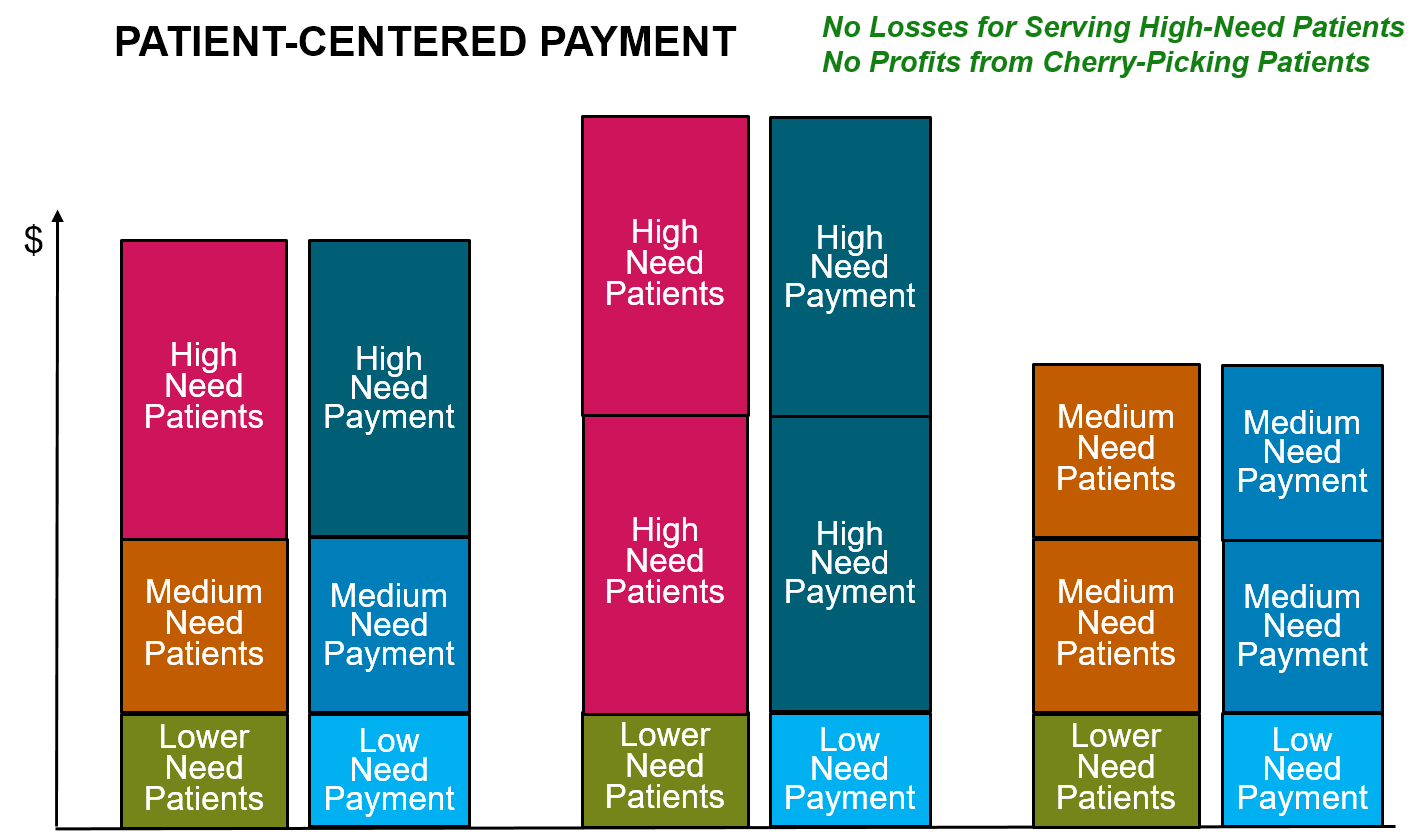

Patient-Centered Payment

Key Elements of Patient-Centered Payment

Current approaches to value-based payment are payer-centered. Their primary focus has been to limit or reduce spending for health insurance plans, rather than to help patients receive high-quality care at the most affordable cost. Current approaches to value-based payment assess whether the average quality of care for the health plan’s members has improved or worsened, not whether each individual patient received high-quality care. Moreover, providers can be financially penalized when they treat patients with higher-than-average needs. As a result, the actions providers must take to succeed under these payment systems can be in direct conflict with doing what is best for patients.

What is needed instead is a patient-centered approach to value-based payment, one that will solve the problems in current fee-for-service payment systems without reducing access to services or the quality of care for patients.

In a Patient-Centered Payment system:

A patient is able to receive the services that will best address their specific health problems. In order for patients to receive the highest-value care, the many gaps in the services eligible for payment under current fee-for-service systems have to be filled. For example, the biggest transformation in healthcare delivery in decades was the dramatic expansion of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic. None of the current value-based payment systems had supported this. It only happened because Medicare and health insurance plans began paying fees for these services for the first time. In a patient-centered payment system, providers should be paid for delivering the types of services that patients need in the way that will work best for the patient.

Each patient is assured of receiving appropriate, evidence-based care. In a patient-centered payment system, in order to be paid for delivering a service to a patient, a healthcare provider should be required to meet an appropriate standard of quality for that specific patient:

- If a desired outcome of the service is within the control of the provider, the provider should only be paid if the outcome is achieved.

- If a desired outcome is significantly affected by factors outside the control of the provider (e.g., a patient’s ability or willingness to follow a particular course of treatment), the provider should only be paid if the services are consistent with evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (unless there are no relevant guidelines or there are good reasons to deviate from them), and if the provider monitors the desired outcome so services can be modified for patients who are experiencing problems. If a provider cannot control whether an outcome is achieved, attempting to hold the provider accountable for the outcome is more likely to discourage the provider from treating high-need patients than it is to improve outcomes for those patients. In general, the best way for a patient to achieve a good outcome is to receive the services that evidence indicates will be most effective.

A healthcare provider receives adequate resources to support the cost of delivering services in a high-quality, efficient manner. No business can deliver a high-quality product unless it is paid enough to cover the costs of producing that product; similarly, a healthcare provider cannot be expected to deliver the kinds of services each patient needs in a high-quality way unless the payments it receives for its services are sufficient to cover the costs of doing so. Moreover, just like any business, a healthcare provider is less likely to deliver a high-quality service if it is paid more for delivering a low-quality service. In a patient-centered payment system:

- a provider’s payment should be based on what it costs to deliver high-quality care, not based on the fees paid in the past, the amount of savings that has been produced, or an arbitrary percentage of total spending.

- a provider should be paid more for patients who need more services or services that cost more to deliver.

- the patient or payer should not have to pay more because of errors and complications that the provider could have prevented.

A patient can select a provider or team based on the quality and cost of the care they deliver. Different patients have different needs and they will require different sets of services to address those needs. No one healthcare provider or health system will be the best at delivering all of the services an individual patient may need or for treating a particular health problem for all types of patients, so if patients are forced to receive services from providers in the same health system or from a “narrow network” chosen by a health insurance plan, some patients will not receive the best care possible. There is no simple measure of “value” that can be used to rank-order providers, because quality is multi-dimensional and cannot be converted into a dollar amount that is directly comparable to costs. Consequently, in a patient-centered payment system:

- providers should define in advance how much a patient or payer will have to pay for care of a patient’s specific health problem and the standard of care or outcomes the provider commits to deliver in return for that payment;

- each patient should be able to choose which provider will deliver their care based on information about both (a) what it will cost for the provider to treat the patient’s health problem and (b) the outcomes and approach to care delivery that are most important to the patient.

Comparison to Current Payment Systems

Patient-Centered Payment addresses all of the problems with current fee-for-service payment systems without causing the additional problems created by current approaches to value-based payment:

- Patient-Centered Payment would fill the gaps in current Fee for Service systems by paying adequately for the services patients need, including proactive wellness care and care management designed to help patients stay healthy and reduce avoidable services. Physicians, hospitals, and other providers would have the flexibility to deliver services in whatever manner works best for an individual patient.

- Compared to Pay for Performance programs, Patient-Centered Payment would assure that every patient receives high-quality care, not just a majority of patients, and not just the subset of patients for whom current quality measures are applicable. The provider of care would be able to deliver the services that will achieve the best outcome for each patient, and they would be accountable for doing what is feasible to achieve, not for things they cannot control.

- Compared to Shared Savings/Downside Risk programs, in a Patient-Centered Payment system there would be no reward for stinting on necessary care, nor would there be a penalty for delivering more services or more expensive services to patients who need them. Physicians, hospitals, and other providers would be paid for delivering appropriate, evidence-based services, and they would not be paid for inappropriate or poor-quality services.

- Compared to Population-Based Payment and Capitation programs, Patient-Centered Payment would provide payments that are adequate to enable providers to deliver appropriate, high-quality services to address each of their patient’s needs, including patients with acute health problems, new chronic conditions, and/or barriers to receiving services in traditional ways. Physicians and hospitals would only be paid if they actually address a patient’s needs.

Patient-Centered Payments for Specific Types of Providers

Patient-centered payments should be based on the types of health problems patients have and the services needed to address those problems, not which provider delivers the care. Payments should be higher if the cost of treating a specific condition or patient is higher, not simply because the services are delivered by a particular type of provider. In contrast to current fee-for-service payment systems, if a patient with a particular health problem can be appropriately cared for by either a primary care practice, specialty care provider, or hospital, the payment should be the same regardless of which provider delivers the care.

However, while many types of conditions can be treated and managed by a primary care practice, and some types of care can best be provided by a primary care practice, some types of conditions and patients require the services of a specialty care provider. In addition, while many types of conditions can be appropriately treated and managed in a physician’s office, in an ambulatory surgery center or other outpatient facility, or in a patient’s own home, some types of services and treatments for some types of patients can only be provided in a hospital or other inpatient facility.

In order to ensure that all patients can receive the most appropriate care for their specific needs, a patient-centered payment system needs to be designed in a way that ensures primary care practices, specialty care providers, and hospitals receive adequate payment to support and sustain the types of services only they can deliver or that they deliver more successfully than others.

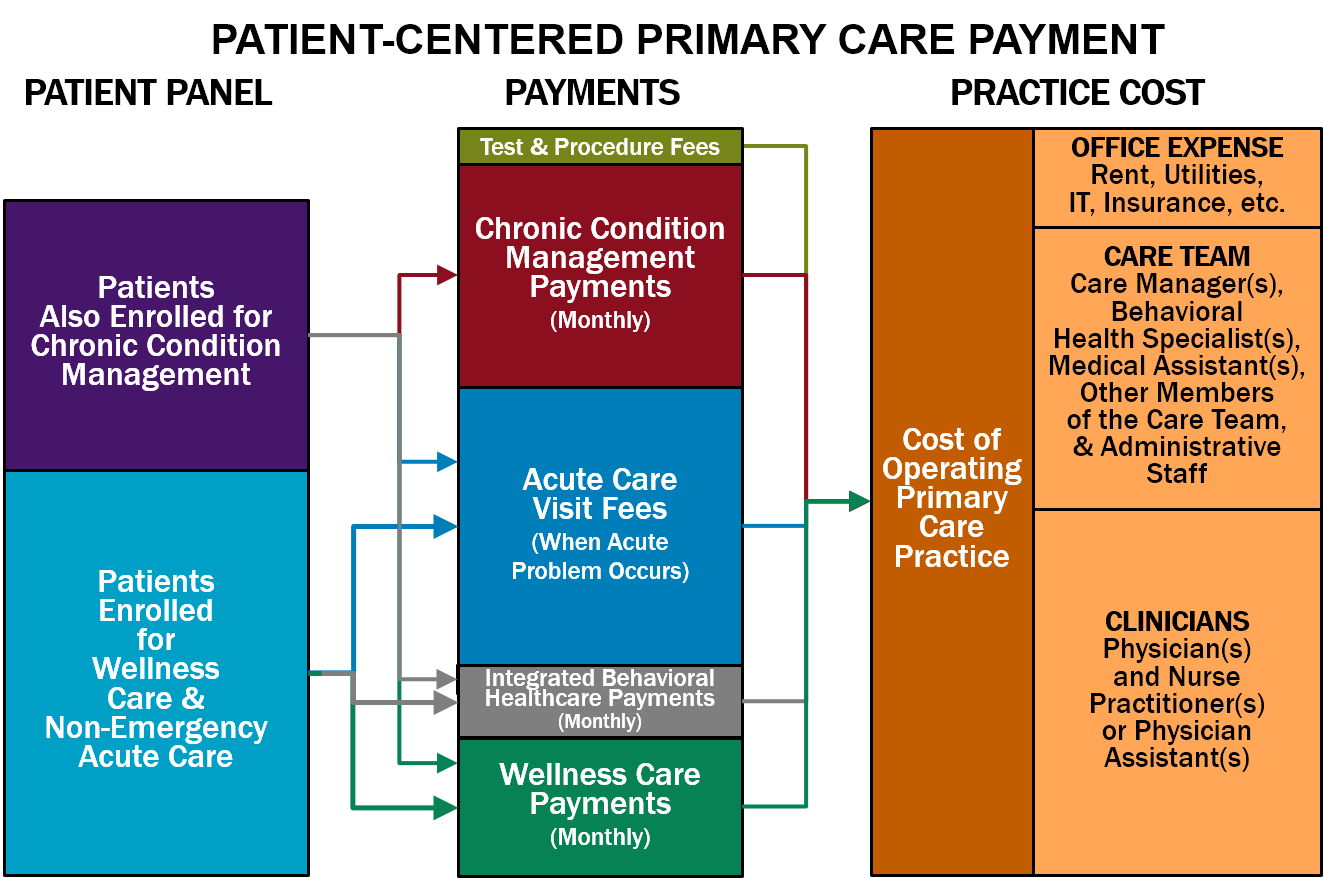

Patient-Centered Payment for Primary Care

Primary care is an essential component of a high-value healthcare system. Primary care practices deliver three important types of services to patients:

- Wellness Care. Primary care practices help patients stay healthy by educating them about what they should do to maintain and improve their health and by ensuring that patients have obtained appropriate preventive care services, such as vaccinations and cancer screenings.

- Chronic Condition Management. For patients who have one or more chronic diseases or long-term health problems, primary care practices not only prescribe appropriate treatments but also help patients understand how best to manage their condition(s) in a way that minimizes the number and severity of complications and slows the progression of the disease.

- Non-Emergency Acute Care. For patients who experience a new symptom or have an injury that does not require emergency care, the primary care practice can either diagnose and treat the problem or arrange for the patient to receive appropriate testing and treatment from other healthcare providers.

Ideally, primary care practices would also provide:

- Integrated Behavioral Health Services. Patients who have both behavioral health needs and physical health needs should be able to have them treated and managed in a coordinated way.

Neither the current fee-for-service system nor current value-based payment systems provide payments to primary care practices that are appropriately structured or adequate in size to support and sustain these services. As a result, there is a large and growing shortage of primary care physicians in the country, many primary care physicians are burning out, and most medical students don’t want to go into primary care.

In a patient-centered payment system, a primary care practice should receive adequate payments for each of these types of services in order to ensure that: (1) each patient can receive high-quality care appropriate for their specific needs, and (2) primary care practices with different types of patients receive sufficient revenues to cover the costs of the services their patients need.

Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment should consist of:

- Monthly Payments for Wellness Care. Maintaining and improving health is a continuous process that occurs throughout the year, not simply through occasional office visits. This proactive care should be supported by a monthly payment for each patient who enrolls with the primary care practice to receive wellness care. The monthly payment would support wellness care management; service-specific fees should continue to be paid for any procedures, tests, or treatments the patient needs as part of their wellness plan, such as immunizations, mammograms, colonoscopies, etc. (In some cases, these procedures, tests, and treatments may be delivered by the primary care practice, but in many cases, a specialty care provider will provide these services.)

- Monthly Payments for Chronic Condition Management. If a patient with one or more chronic conditions (such as asthma, diabetes, or hypertension) wants the primary care practice to help manage those conditions, the practice should receive an additional monthly payment for that patient in order to deliver chronic condition management services. Since continuous, proactive care is needed to reduce the severity of symptoms and prevent exacerbations of the condition, a monthly payment is necessary to support this. A higher monthly payment will be needed during the initial month following diagnosis or enrollment in order to develop the most effective treatment plan and to ensure it is effective, and a higher monthly payment will be needed for a patient with a combination of chronic conditions or other characteristics that require significantly more time and assistance. Some patients with a chronic condition will need or want to receive support from a specialty care provider, particularly patients with severe conditions and patients for whom standard treatments are not effective or have problematic side effects. Consequently, the primary care practice should only receive a monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment for a patient who explicitly enrolls with the primary care practice to receive chronic care management.

- A Fee for Diagnosis and Treatment of a Non-Emergency Acute Event. Some patients who are receiving good preventive care and chronic disease management will have accidental injuries, acute illnesses, or problematic symptoms that will require additional services from the primary care practice. Since these events will occur unpredictably, and different patients may be more susceptible to these problems than others, the primary care practice should receive an Acute Care Visit Fee when it provides diagnosis and treatment services for a new acute event. The practice should be permitted to deliver services in whatever way is most appropriate in the circumstances, including by telephone, telehealth, or an in-person visit with the physician or other practice staff. The Acute Care Visit Fee would not be paid for care of a patient experiencing an exacerbation of a chronic disease, however, since the cost of that kind of care would already be covered by the monthly payment for chronic condition management.

- Monthly Payments for Integrated Behavioral Healthcare Services. Primary care practices that deliver integrated behavioral health services to their patients need to employ or contract with staff who have training in helping patients with behavioral health needs. In order to support this, the practice should receive an additional monthly payment for each patient who is enrolled to receive wellness care from the practice.

- Fees for Individual Procedures and Tests. Many primary care practices also perform procedures such as an immunization, injection, or excision and/or perform basic laboratory tests. It is beneficial for patients to be able to receive these procedures and tests from the primary care practice if possible, rather than needing to make a separate trip to another physician or facility. Since only a subset of patients will need these procedures and tests, and since the cost of performing each of them will differ, the primary care practice should receive an additional fee when it performs a procedure or test that is adequate to cover the cost.

In order to assure that each individual patient receives appropriate, high-quality care, a primary care practice should be required to:

- Deliver Evidence-Based Care. The primary care practice should only bill and be paid for a Monthly Wellness Care Payment, Monthly Integrated Behavioral Healthcare Payment, Monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment, or Acute Care Visit Fee if the practice delivered all appropriate services to the patient during the month or acute care visit that are consistent with applicable, evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) or the practice had documented the reasons for deviation from those guidelines in the patient’s clinical record; and

- Monitor Patient Needs and Outcomes. The practice should only bill for and be paid the monthly payments if it used a Standardized Assessment, Information, and Networking Technology (SAINT) to identify and prioritize any problems the patient is experiencing and to determine whether the practice’s services are effectively addressing the patient’s needs. For example, How’s Your Health is a SAINT specifically designed for primary care that is used by many small practices.

The payment amounts should be based on the estimated cost for a primary care practice to deliver each category of service, considering the amount of time needed to deliver evidence-based services, the types of personnel who are most appropriate to deliver the services and their compensation levels, and non-personnel costs such as information systems, equipment, and space. The following amounts would likely be needed by most primary care practices to deliver high-quality care:

- a $7.40 Monthly Wellness Care Management Payment for each patient enrolled for wellness care.

- a $4.25 Monthly Integrated Behavioral Healthcare Payment if the practice offers integrated behavioral healthcare services.

- a $30.60 Monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment for each patient with a chronic condition who is enrolled with the practice for chronic condition care.

- a $141 Acute Visit Fee for a patient who has a new acute problem (not related to a chronic condition).

For patients with insurance, cost-sharing amounts should be established that enable and encourage patients to use the primary care practice:

- A modest co-payment for acute care visits;

- No cost-sharing for wellness care; and

- No cost-sharing for chronic condition management.

Summary of Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment

More Details on Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment

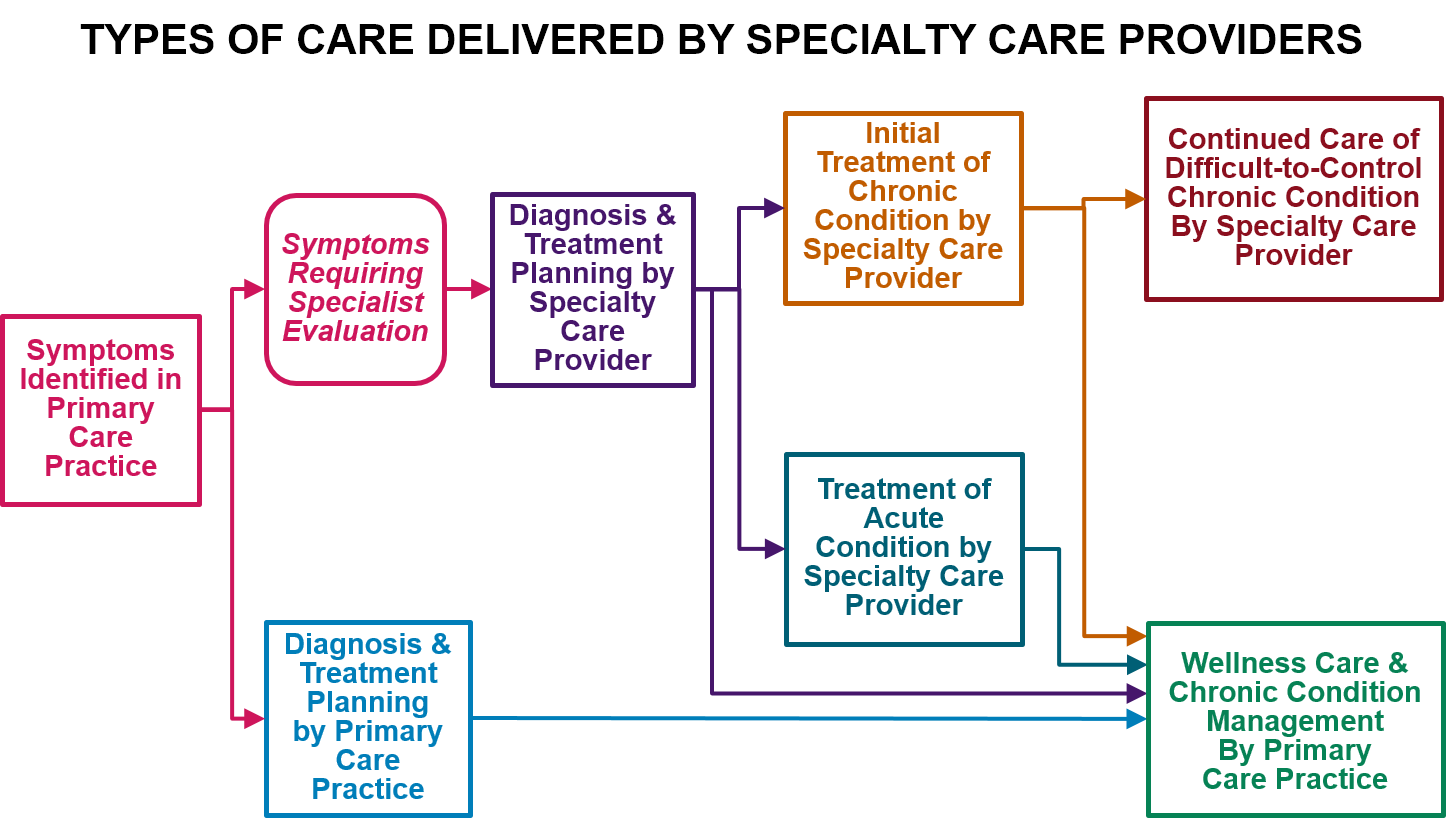

Patient-Centered Payment for Specialty Care

Many patients have health problems that require specialized expertise to diagnose or treat. Specialty care providers deliver three types of services that complement the work that primary care practices do:

- Diagnosis and Treatment Planning. In some cases, it is difficult to determine the cause of a patient’s symptoms without specialized training and experience. An inaccurate diagnosis can lead to unnecessary or harmful treatment for a non-existent problem and/or failure to properly treat the real problem. In addition, many patients receive unnecessary tests and/or unnecessarily expensive tests to rule out unlikely diagnoses. In some cases, these tests can lead to false positive results that contribute to inaccurate diagnoses and unnecessary treatments.

- Management of Chronic Conditions. Although many chronic conditions can be managed effectively by a primary care practice, some patients with a chronic condition will need or want to receive support from a specialty care provider, particularly patients with severe conditions, including serious behavioral health conditions, and patients for whom standard treatments are not effective or have problematic side effects. In addition, some patients with a chronic condition may need to temporarily receive treatment and proactive management services for that condition from a specialty practice rather than the primary care practice, such as when the patient experiences an acute condition that complicates management of the chronic condition (e.g., the patient becomes pregnant and the medications she had been taking for the chronic condition are problematic during pregnancy).

- Treatment of Serious Acute Conditions. Treatments and procedures for serious acute conditions may require not only special expertise, special equipment, or special facilities to perform, but multiple providers may need to contribute components of the necessary care. For example, a patient who needs surgery will require the services of a surgeon, an anesthesiologist, a hospital, and potentially other physicians and post-acute care providers in order to achieve the best outcome. All of these providers have to work together as a team if the patient is to receive care in the most effective, efficient way.

Many current value-based payment systems try to discourage the use of specialty care regardless of whether patients need it or not, or they penalize the use of expensive components of specialty care (e.g., drugs or rehabilitation) in ways that can be harmful to the patients who need those types of services. There are very few value-based payment systems specifically designed to support high-quality specialty care, particularly ambulatory specialty care.

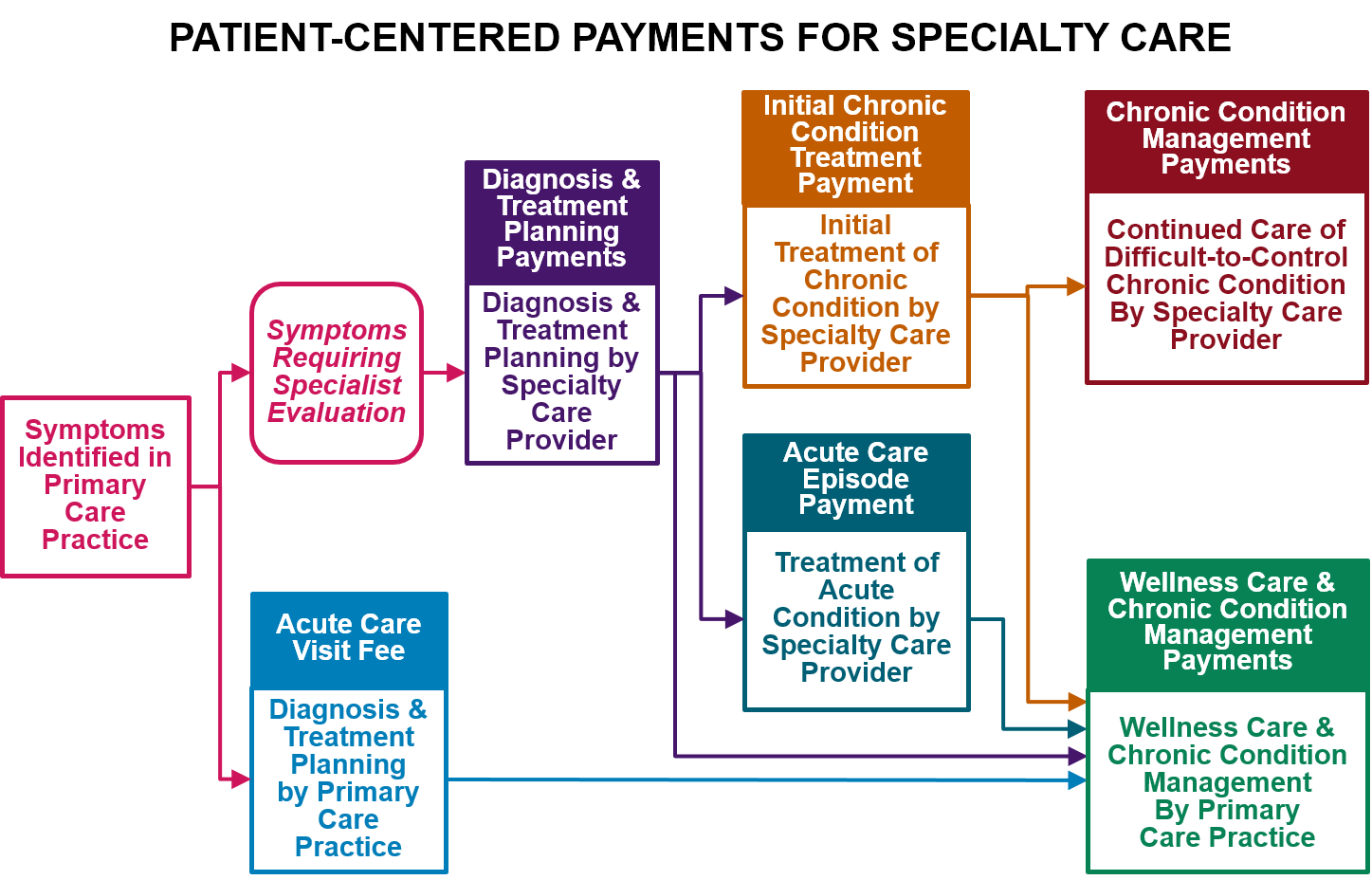

In a patient-centered payment system, payments should enable patients to receive services that require specialized expertise, and the payments should encourage a team-based approach to specialty care delivery when multiple providers are involved. No one payment method can support all types of care for all patients.

Patient-Centered Payment for Specialty Care will require four different types of payment:

- Payments for Diagnosis and Treatment Planning. A physician (or team of physicians) with expertise in diagnosing the cause of a specific symptom or set of symptoms should receive a one-time Diagnosis Payment to support the time involved in determining an appropriate diagnosis. In cases where the same symptoms could result from very different kinds of problems, separate payments to two or more specialty providers may be necessary. If the patient is diagnosed with a specific health problem, there should be an additional Treatment Planning Payment to support the time needed to work with the patient to plan an appropriate treatment. If the patient’s symptoms can be diagnosed by a primary care practice, the Acute Care Visit Fee would serve both of these functions, but if the primary care physician determines that a patient needs to see a specialty provider for diagnosis and/or treatment planning, these separate payments would support the specialty provider’s services.

- An Episode Payment for Treatment of Common Acute Conditions. For common acute conditions where there is an evidence-based protocol for treatment, such as many types of surgeries for patients with no unusual characteristics, the team of providers delivering the treatment should receive an Acute Condition Episode Payment, i.e., a single “bundled” payment for all of the services that all of the providers deliver in order for the patient to receive all components of appropriate, evidence-based care for the condition. The amount of the payment should be based on the cost of the specific services that need to be delivered.

- Monthly Payments for Management of Chronic and Extended Acute Conditions. Similar to chronic conditions managed by primary care practices, if a patient enrolls with a specialty provider for ongoing assistance in treating and managing a chronic condition, that provider should receive a Monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment for that patient to support delivery of appropriate chronic condition management services. Since continuous, proactive care is needed to reduce the severity of symptoms and prevent exacerbations of the condition, a monthly payment is necessary to support this. Monthly payments are also appropriate for patients with an acute condition that will require focused treatment or management over an extended period of time, but where the exact length of treatment is uncertain or the intensity of treatment may vary from month to month, such as patients with cancer and women who are pregnant. Higher monthly payments will be needed for patients with a combination of chronic conditions or other characteristics that require significantly more time and assistance, and higher payments will be needed when treatment first begins.

- Payments for Coordinated Treatment of Uncommon or Complex Conditions. For patients who have an uncommon acute or chronic condition or who have other characteristics that require special approaches to treatment, it may be either impossible or inappropriate to prospectively define an episode payment or monthly payment for their treatment. In these cases, the members of the provider team treating the patient should receive (a) fees for each of the individual services they deliver, and (b) a Treatment Coordination Payment to ensure that all of the services are effectively coordinated and that quality standards are met.

In order to assure that each individual patient receives appropriate, high-quality specialty care, a specialty provider or team of providers should be required to:

- Deliver Evidence-Based Care. The specialty provider team should only bill and be paid for a Diagnosis or Treatment Planning Payment, a Monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment, an Acute Condition Episode Payment, or Treatment Coordination Payment if the patient had received all services that are consistent with applicable, evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) or the provider had documented the reasons for deviation from those guidelines in the patient’s clinical record.

- Monitor Patient Outcomes. The provider should only bill for and be paid for services if it used a Standardized Assessment, Information, and Networking Technology (SAINT) to monitor whether the treatments and services delivered are achieving the desired outcomes.

- Achieve Outcomes Within the Control of the Provider. If a specific outcome can be defined that is desirable for the patient, feasible to achieve, and under the control of the provider or team of providers treating or managing the patient’s health condition, then the provider team should also be held accountable for achieving that outcome in order to receive payment for their services. However, this will generally only be possible for patients with a common chronic or acute condition and no special characteristics.

- Contribute Information to a Clinical Data Registry. Data on outcomes achieved for patients are essential for developing the evidence necessary to fill the gaps in current clinical practice guidelines and to update the guidelines as new treatments and approaches to care delivery are developed. Participation in a Clinical Data Registry enables information on services and outcomes from multiple providers to be assembled in a way that supports analysis and research on the effectiveness of different approaches to diagnosis and treatment for patients with specific characteristics.

The amounts of payments should be based on the estimated cost for a specialty provider or team to deliver the care during a month or episode of care, considering the amount of time needed to deliver evidence-based services, the types of personnel and facilities that are most appropriate to deliver the services, the cost of drugs and medical devices used for treatment or condition monitoring, the cost of collecting outcome data and participating in a clinical data registry, and other costs such as equipment, utilities, and space.

For patients with insurance, cost-sharing amounts should be designed to enable and encourage patients to receive services that improve outcomes and to use providers that deliver good outcomes at a lower cost.

Summary of Patient-Centered Payment for Specialty Care

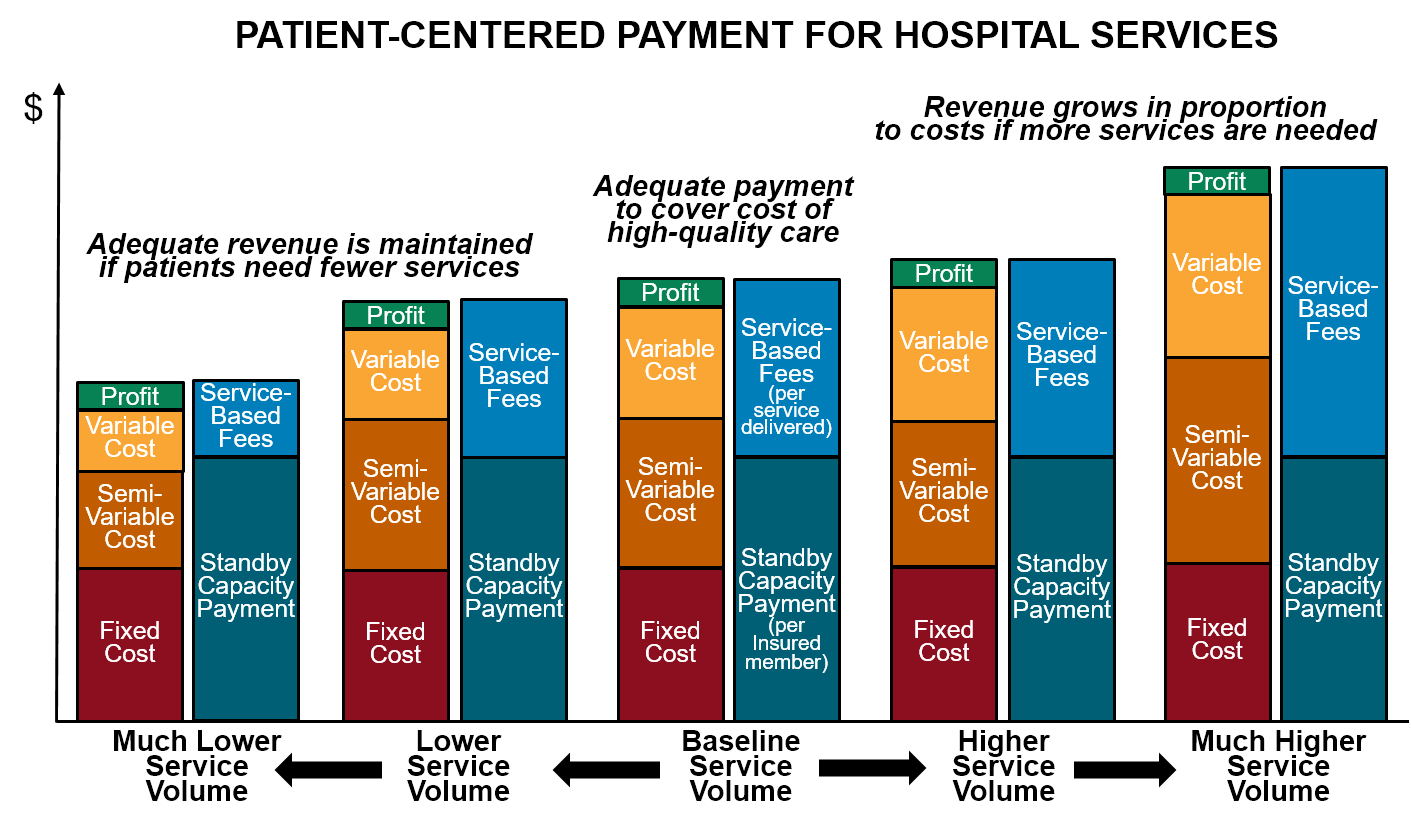

Patient-Centered Payment for Essential Hospital Services

Most current value-based payment systems are specifically intended to reduce the frequency with which patients receive hospital services, since research has shown that many of the biggest opportunities to improve quality and reduce spending involve reducing avoidable hospital admissions and delivering services in ambulatory care settings or patients’ homes. Success under these value-based payment models means hospitals will receive lower revenues, but none of the current payment models attempt to ensure that hospitals will continue to receive enough revenues to support high-quality care for the smaller number of patients who will still need hospital care:

- There is a significant fixed cost associated with each hospital service line, which means the average cost of delivering an individual service will be higher when fewer services are delivered. Because most current value-based payment systems continue to pay for individual services using standard fee-for-service payments, and the fees are typically based on the average cost of services at current volumes of service delivery, a reduction in the number of services delivered will cause a hospital’s revenues to decrease more than its costs will decrease, particularly in the short run, causing a financial loss.

- Moreover, the patients who will continue to need care in a hospital will be the most complex patients, who are more expensive on average to care for, causing the financial loss to be even greater.

These financial losses could reduce access to hospital services for the patients who still need them. This is particularly a problem for small and rural hospitals, which do not make large profits on individual services that can offset the losses from reductions in the number of services delivered. These hospitals could be forced not just to eliminate services, but to close entirely.

Under a patient-centered payment system, most of the payments for hospital services would come from the hospital’s share of Acute Condition Episode Payments for procedures and treatments delivered in the hospital and payments for individual services delivered in the hospital for uncommon and complex conditions, and the amounts of these payments can be set at levels designed to cover the cost of delivering the services to the number and types of patients who need to receive services in a hospital. However, in addition to specific procedures and treatments, a hospital delivers an important set of services to the community that are not directly supported by current fee-for-service payment systems and that would not be adequately supported through the patient-centered payments for primary care or specialty care:

- Emergency Services. A hospital emergency department must be adequately staffed and equipped to handle rare events such as serious accidents, natural disasters, infectious disease outbreaks, etc., while also hoping that no such events actually occur. In addition, in a small commmunity, the emergency department must be staffed on a round-the-clock basis even though there may be few or no visits at certain times of the day, and it has to have adequate capacity to handle multiple visits at a time when they do occur. Providing this “standby capacity” is an important service that all of the residents of the community benefit from, but there are currently no payments explicitly designed to support it.

- Other Essential Standby Services. In addition to the emergency department, certain other hospital departments, such as a cardiac catheterization unit, a labor and delivery unit, a radiology department, a laboratory, and/or a surgery suite, must be staffed and ready to quickly respond to heart attacks, strokes, premature births and complications of labor, major trauma, sepsis, etc. on a round-the-clock basis even if some of those situations occur only occasionally, particularly in small communities. The hospital also needs a minimum level of inpatient care capacity so that it can admit patients who cannot safely be discharged home. Providers of ambulance services and specialized non-emergency transportation (such as wheelchair vans for disabled individuals) must have slack capacity in order to be available when needed. All of these services require that essential personnel and equipment are standing by in case a patient needs them, but there is no payment explicitly designed to support this standby capacity.

Since there are currently no payments specifically designed to support standby capacity, the hospital or other provider has to cover the costs through the profits on other services it delivers. This encourages the delivery of unnecessary services and/or charging prices higher than costs. Not only are these strategies undesirable and often unsuccessful, they are even less feasible in a value-based payment system where primary care practices and specialty care providers are delivering care to patients outside of hospitals whenever appropriate. Consequently, a better way to pay for these standby services is needed.

Since standby services provide a benefit both to individuals who potentially need them as well as those who actually receive them, a patient-centered payment system needs to have a component to enable “potential patients” to support the standby capacity costs:

- Standby Capacity Payment for Essential Services. A hospital that provides essential standby services should receive a Standby Capacity Payment from each health insurance plan (Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and commercial insurance) based on the number of members of that plan who live in the community served by the hospital (regardless of whether the member receives a service). The amounts of the payments should ensure that the hospital has adequate revenues to support the minimum standby costs of essential services such as the emergency department, inpatient unit, and laboratory regardless of how many patients actually need services during any given month or year. Other providers that deliver services that require significant standby capacity (such as ambulance services) should also receive Standby Capacity Payments designed to cover their minimum fixed costs.

If a hospital or other provider receives Standby Capacity Payments to cover the fixed cost of operating a service line, there would still be a need for an additional payment when a service is actually delivered in order to cover the variable or semi-variable costs of the service (i.e., the costs that are only incurred when an individual service is actually delivered, such as the administration of a drug). This payment should either come from an Acute Condition Episode Payment or a payment specifically for a specialized service. However, the amount of this per-service payment would be much lower than current fees for such services since it would be based on the marginal cost per service (i.e., the magnitude of the variable cost component), not based on the average cost of the service as fee-for-service payments typically are today. This will help make essential hospital services more affordable for patients, particularly those without insurance.